ZORBA THE GREEK, Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά, NIKOS KAZANTZAKIS: LETTING THE VIRGINITY OF THE WORLD RENEW ITSELF.

An interval of more than fifty years. First the music – then the dance – much later the film – and even much later the novel in itself. In the mid-1960s the dance of the film Zorba the Greek (1964), composed by Mikis Theodorakis, Μιχαήλ Θεοδωράκης (*1925 – †2021), was enacted in every corner of the world. Even in the smallest towns of the small South American Republics you could see girls and young women showing off with the elaborate steps of the sirtaki, συρτάκι. As far as I can recall, I only saw the film (which enjoyed a monumental commercial success, world-wide) for the first-time in the late 1970s in London. And it was much later, in 1998, that I decided to confront the novel in itself, in a French version, while sojourning in the most suitable place on earth for such a reading: Crete.

I wrote in my diary, just while throwing myself into the first pages of Zorba:

10.09.1998. I took refuge in a tavern in the small town of Kavros. It is a pity that they indulge in “techno” music. I prefer the noise of the cars passing by outside. They have a more original rhythm.

“Zorba the Greek”, The great homage of Kazantzakis to Crete, the Crete of the “African coast”. (...)Afterwards came the film – London? - of which I keep the memories of the French Madame, of those ladies who rampaged through her house after her death, of the splendid widow interpreted by Irene Papas, as well as the face of Anthony Quinn, and the Orthodox priests.

And now, 25 years after that first reading, I was seized by a calm curiosity as to how would I react at my second reading in French, this time accompanied by the Greek original, after the sloppy infatuations with girls dancing the in the 1960s, the film version by late 1970s, and those two weeks in Crete, were I was being transported like a cloud through the paysages and the people that inspired Kazantsakis.

The film, directed by Michael Cacoyannis (who also wrote the screen-play) is based on the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis (Νίκος Καζαντζάκης, (*1883-†1957), published in 1946 as Life and Times of Alexis Zorba (Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά). It starred Anthony Quinn as Zorba, a most suitable selection, as he was in fact born as Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca, a “Mexican-American”, who only obtained American citizenship in 1940, (*1915-†2001). With a father born in Ireland. who fought for Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution, and his mother being a Mexican woman who got pregnant as a 16-year girl, all the basic ingredients were there to incarnate a boisterous Macedonian Greek, who fought against the Turks, escaped to Russia, came back, was a self-made miner, loved his santouri and danced as often as pious people go to church. Not to be forgotten: a heavy womaniser.

First encounter at Piraeus, Basil and Zorba.

------------------------------------------------------

There is Irene Papas (1929-2022), appearing as the “widow”, Alan Bates (1934-2003) plays the role of Basil, the Englishman whose father was born in Greece, and Lila Kedrowa, French-Russian, (1918-2000) appears as “Madame Hortense”, a stupendous performance which won her an Oscar for best supporting actress.

The first-person narrator in the novel, whom we might describe as an “alter ego” of Kazantzakis, would say to himself that “she looks like Sarah Bernhardt, when she was of the same age...”

------------------------------------------------------

Madame Hortense, is an aged French lady who runs a small alberge in a village where Zorba and the first-person narrator will install their provisional headquarters. She has retired to that isolated part of the island, and keeps remembering her “golden years”, when the entire Mediterranean sea was the manoeuvring room (rather bed) of her ars amatoria, including the chief-admirals of the French, Italian, Russian and English fleets. She claims to have saved Crete and their inhabitants from incessant bombarding, as the admirals were keener on spending time with her, but:

"How many times the woman you see here has saved the Cretans from death! How many times the guns were ready loaded and I seized the admiral's beard and wouldn't let him 'boom-boom!' But what thanks have I ever had for that? Look what I get in the way of decorations…" 1

The film is based on the novel, but it is not the novel.

Let us just sum up the “film”. An Englishman, a writer whose father was Greek, comes to Crete to attempt to revive an old mine which belonged to his father. In the port near Athens, he meets Alexis Zorba, a former warrior and miner. Both struck immediate friendship, and they take residence in the pension of Madame Hortense. She and Zorba soon start a passionate love-affair. The lignite mine is unsafe, Zorba thinks about using the forest on a nearby mountain, in possession of a monastery, for logging. The thus freshly obtained wood will be used to shore up, to consolidate the tunnels of the mine. Construction of a rudimentary cable-car starts, to bring the logs down to the beach. Basil finally decides to spend one night with the beautiful “widow”. The event is witnessed by someone who soon rumours it to the whole town, provoking the death of a young man, who in love with the “widow”, prefers to commit suicide. His family is going to take a cruel revenge on the “widow”, by cutting her throat.

Madame Hortense dies, the ladies of the town rampage through her rooms, stealing every valuable thing. Zorba’s concocted artifice for the transportation of logs ends in a catastrophe. At his petition, Zorba teaches Basil how to dance, on the beach, to liberate his body and his soul from failure.

There are substantial differences between the 1964-film and the text of the novel as such, above all concerning the substrata permeating the novel in every page. And for those who are only aware of the film, it is indeed advisable to visit the novel, as they would be able to gauge the “naked rawness” of life in Crete, at that time (1929). Crete, that island which was perhaps the most remarkable melting-pot between Europe and Africa, between the Greeks and Turks, the Arabs and Christians, the Jews and the Muslims.

The film does respect, to a large extent, the linear narration of the main events contained in the original novel, yet it does mutate the first-person narrator (“a young Greek intellectual”) into an uptight Englishman, in principle a writer, half Greek (his father was born in Greece), yet also half a tourist. Such an alteration did indeed procure the film a saleable glamour, and accentuated the contrast between the supposed reservedness and naive incomprehension of an upper-class Englishman, who almost always wears a suit, and the boisterous spontaneity of the Cretans, splashing joie-de-vivre and hospitality, on the sly though carrying the seeds of unpredictable, violent roughness, leading to tragedies. We have then a watered-down, much better parfumated, indeed almost flashy glamorous drama

The first encounter between Basil (Alan Bates) and the "widow" (Irene Papas), as Basil gives her his umbrella. ------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------

The novel aims much, much higher.

The novel aims much, much higher – and it does attain those proposed peaks. The first-person narrator is a “young Greek intellectual”, Kazantzakis’s alter ego, let us refer to him from now on as alter ego. He is a socialist, but also a patriot, he is a man of spirituality, devoted to his Greek church à sa manière, but also a Nietzschean. When he arrives in Crete, he is reading Dante Alighieri’s Divina Comedia (his “travel companion”2) , and writing an essay on Buddha It is the year 1929, a friend of his, Stavridakis, who has gone to the the Russian Caucasus to help the local Greek communities facing persecution, set off his decision to abandon the sterile intellectual discussions in Athens, and come to Crete. Stavridakis is to reappear later in the novel.The Alexis Zorba (Αλέξης Ζορμπάς) of the novel is a fictionalized version of the mine worker George Zorbas (Γιώργης Ζορμπάς, 1867–1941), whom Kazantzakis met, as he had indeed attempted to bring back into life an old lignite-mine.

From the first page to the last, the grandeur and the decline, the paradoxes, the ups and downs, the contradictions of the Greek nation (“that marvellous synthesis between Orient and Occident”), and of those Greek communities scattered all around the world, constitute one of the main Leitmotive.

Stavridakis reappears later in the novel, sending a letter:

“Half-a-million Greeks are in danger in the South of Russia and the Caucasus. A lot of them speak only Russian or Turkish, but their heart speaks Greek with fanaticism. They are of our blood. (…) … they are the true descendants of your beloved Ulysses. Hence we loved them and we are not going to let them die. (…) Because they are in danger of dying. They lost everything they once had, they are hungry, they are naked. On one side they are being persecuted by the Bolsheviks, on the other by the Kurds. Refugees from everywhere have come to be piled up in a few towns of Georgia and Armenia.”3

Yet a different tone comes from another friend in Africa, who also urges alter ego to abandon his books and join him down there. Karayanis, at a mountain near Tanganyika:,

“Politics, that is what ruins Greece. Also the cards, the lack of instruction and the flesh. (…) I hate the Europeans, that’s why I am erring here, amidst the mountains of Vassamba. I hate the Europeans, but, above all, I hate the Greeks and that it is Greek. “

He has already prepared his grave, and the inscription on the tombstone:

“Here lays a Greek who detests the Greeks.”4

The burdensome, still fuming “embraces” between the Turks and the Greeks very much so, as well. One just have to read how Zorba, 65 years old in the novel, describes to alter ego his participation in the war against the Turks in Crete, in 1896, at the age of 32:

"And now I suppose, boss, you think I'm going to start and tell you how many Turks' heads I've lopped off, and how many of their ears I've pickled in spirits— that's the custom in Crete. Well, I shan't! I don't like to, I'm ashamed. What sort of madness comes over us?... Today I'm a bit more level-headed, and I ask myself: What sort of madness comes over us to make us throw ourselves on another man, when he's done nothing to us, and bite him, cut his nose off, tear his ear out, run him through the guts—and all the time, calling on the Almighty to help us! Does it mean we want the Almighty to go and cut off noses and ears and rip people up?”5

Similar descriptions of the carnages and tragedies accompanying the Greeks, and of the small town in Crete, abound in the novel. The scene of the killing of the beautiful “widow” in the film is just marked by the knife of the man approaching the throat of the woman. In the novel the rendering of the episode is rougher and preciser:

“”… he beheaded the woman in one single coup. “I take the sin upon myself!” he screamed, and threw the head of the victim onto the threshold of the church...”6

Humour does also materialise, mostly unexpected.

“Just then, as we entered the village, a beggar-woman clothed in rags rushed towards us with an outstretched hand. She was swarthy, filthy, and had a stiff little black moustache. "Hi, brother!" she called familiarly to Zorba. "Hi, brother, got a soul, have you?" Zorba stopped. "I have," he replied gravely. "Then give me five drachmas!" Zorba pulled out of his pocket a dilapidated leather purse. "There," he said, and his lips, which still had a bitter expression, softened into a smile. He looked round and said: "Looks as if souls are cheap in these parts, boss! Five drachmas a soul!"

------------------------------------------------------

Anticipating the collapse of the old ideas

Written probably in 1996, the blurb on the back-cover of the French edition we read in 1998 states, lucidity and simplicity enjoying their utmost robustness, Kazantzakis’ foresight:

“The Cretan Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957) knew, avant l’heure, that we were at a turning point of the world, where everything is being destroyed and created, where the human being decomposes itself before a new birth. He knew that the old receipts were no longer valid, that it was necessary to take leave from the ideas: “Patrie, religion, science, art, glory, communism, fascism, equity, brotherhood...”7

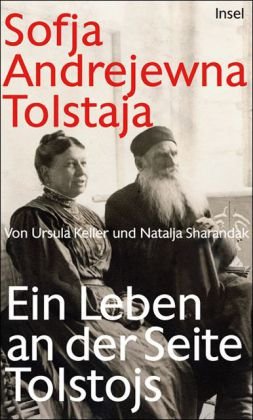

Cover and back-cover of the French edition we read in 1998, and re-read in 2023.

------------------------------------------------------

And that consciousness of being at the crest of a colossal wave, soon bound to destroy the old sand-castles on the beach of mankind, creating a vast emptiness, yet perhaps also planting the seeds of a future present (yet to be imagined), is the intellectual and emotional backbone sustaining Zorba the Greek. A convinced Socialist, close to the Greek communist party, yet never a member, friend of the Soviet Union, yet also to be disappointed by Stalinism, Kazantzakis had a Nietzschean coloratura having translated from German into Greek Thus Spoke Zarathustra, doctoral thesis in Athens and in Paris on Nietzsche. That coloratura he unleashes, with full poetry and full tenderness, onto the Greek-Macedonian Zorba, a sort of Nietzschean Sinbad the Seaman, but speaking rather with a Dionysian accent, a proletarian destroyer of bookish interpretations, mistrusting every theological discourse, a fanatic arguer in pro of carpe diem.

Dance as a way to liberate one’s soul to communicate that which cannot be transmitted by words.

Dance is for Zorba not just an “entertainment”. It is an intimate and rewarding language, which transmits that which cannot be expressed by words. There are many striking, at times hilarious, episodes narrated by Zorba of his sojourns in Russia (then the Soviet Union), yet perhaps the most moving relates to his friendship with an uninhibited Russian, near Novosibirsk. Zorba’s Russian was composed of about six or seven words (no, yes, bread, water, I love you, come, how much?), the Russian’s Greek did almost certainly not surpass four words. Yet they understood and enjoyed each other's company as if they were in paradise. When Zorba did not understand the words of the Russian, then the former stood up and started dancing:

“like a possessed one…” (...)“And I looked at at his hands, his feet, his breast, his eyes, and I understood everything”.8

The famous scene at the end of the film, "let us look into the future, dancing..."

------------------------------------------------------

And here re-surges, again, the rough but core-centred improvised philosopher of language:

“Ah, my poor fellow! Men have sunk very low, may they go to hell! They let their bodies become mute, and they speak only through the mouth. But, what do you expect a mouth to be saying? What could a mouth say? If you could only have seen how the Russian listened to me, from head to feet, and how he understood everything!»9

There is another film in which this conception of “dance” as an intimate dialogue with one’s own soul, and as a way of transmitting that which words cannot transmit. Never on Sunday, Ποτέ την Κυριακή (1960), where Ilya, a prostitute interpreted by Melina Mercouri, (Μαρία Αμαλία "Μελίνα" Μερκούρη, *1920-†1994) had to intervene to stop the fighting between a Greek, who had abandoned himself to his dance in a Greek tavern, and an American scholar (a Hellenist, “Homer Trace”) who applauded the Greek out of admiration, only to unleash his rage.

Ilya tells the American:

“In Greece when a man dances, it is for himself, it makes him better in his soul. He is angry, because by applauding him, you treated him as an entertainer…”

Never on Sunday dwells to some extent on some of the issues present in the Kazantszkis’s novel, in particular the “intellect versus down-to-earthness” parable, as the American scholar, who is looking for explanations of the decline of Greece, will try to extract Melina Mercouri from her existence as a prostitute, while the woman would love to “bring the American scholar” down, to a more humble, more elementary life, “embracing the primary fires of life”, as in the case of Zorba.

“Burn all your books and then we will make something out of you!”

Alter ego leaves a lot of clues throughout the novel of they key philosophical issues he was trying to tackle, then in 1943, as he started the writing of Zorba. The events of that year, and of the nearest ones, do not seem to have biased Kazantzakis in his construction of that particular odyssey through Crete in 1929.

There is a constant attempt to reconcile Western ratio with Oriental psyche (in the Greek meaning of this word), that is why he is writing an essay on Buddha, a permanent confrontation with the grey ideas, on the one hand, and the mineral sound of Greek light, as materialised in Crete. He also dialogues with Zorba, asking him to many “whys” and “what-fors”, who then makes him a clear-cut proposal:

“I am going to tell you an idea which just came to me, patron, but you must not be angry: put all your books together, and then light a fire. After that, who knows, you are not an idiot, you are a brave guy … we may be able to make something out of you!.

“He is right, he is right! I screamed within me. He is right, but I cannot!”10,

Not few readers were tempted, and perhaps nowadays they still are, to classify Kazantzakis’ novel as an entertaining, intellectual eulogy of the “bon sauvage”. It is indeed not such an attempt, but readers may be enticed onto such a road by the word “primitive” (English and French versions), which appears quite often in the text, in particular when the Kazantzakis’ alter ego, attempts to de-cipher Zorba.

“When I had finished reading Zorba's letter, I remained undecided for quite a while. I did not know whether I should be angry, or laugh, or just admire this primitive man who, by removing the crust hiding life—logic, morality, honesty—attains its very substance. All the little virtues, so useful, were not present in him. He only had an uncomfortable, difficult dangerous virtue, which urges him irresistibly towards the utmost limits, towards the abyss.”11

πρωτόγονος άνθρωπος (Νέα ελληνικά) is usually translated as “primitive human-being” (the word anthropos in Greek includes both male and female), πρωτό being “first” (which relates to the Latin origin of “primitive”, “primus”, “the first''), γόνος possessing the meaning of “son” or “offspring”, or “creature”, but also that of “sperm”, “pollen”. Zorba is not a “primitive” (in the sense the word is used (or rather frequently misused) today, not the uneducated-one, le bon sauvage, but someone who bath in in the first elements, whose backbone is constituted of those primaeval forces which render a human-being healthy, agile, always fresh, always curious, the sea, the sun, the wind, bread, music, hard work, long voyages and, in the case of Zorba… women.

Perhaps a more pertinent description:

“Like a child, he sees everything for the first time. Persistently he gets surprised and interrogates. Everything appears to him as a miracle, and, every morning, when he opens his eyes and sees the trees, the sea, the stones, a bird, he remains with his mouth shut ”12.

He boasts that the only book he has ever read was Sinbad the Seaman.

Already in Crete in 1998 I felt uncomfortable about the utilization of the word “primitive” in the French version. In my “Cretan” diary, near to the paragraphs and phrases I copied by hand from the French translation, I attempted a first re-interpretation (in German), opposing “primitif” to “barbarisch”, the latter qualified as “foreign” and “destructive”, the former being upgraded as “back (a return) to the Elements...”

It is worth revisiting another paragraph, to understand while “primitive” in this case should be substituted by a “man of the first-Elements”, “the origin in itself“, “the eternal recourse to the basics”. This is the reaction of alter ego, while listening to Zorba eulogising the “red wine”, “What on earth is again this prodigious liquid? You drink this red juice and, see, it is your soul which expands, it does no longer fit in the old carcass , it defies God to a fight. What is this, patron, tell me?”13:

So it is the “origin in itself” which keeps reappearing, renewing itself. To be noticed that in the English version the Greek word for “virginity” is translated as “pristine freshness” - not at all a bad suggestion.

The Cretan landscape as an example of “good prose”

On the 14th of September 1998 I wrote in my Cretan diary:

“Finished the “Alexis” by Kazantsakis the day before yesterday, a novel deeply rooted in his biography. In 1917 he attempted - and failed - a mining project - Lignite - with a "Georges Zorba".

One tends to describe the leitmotiv of the opus as the contradiction - and at the same time the fascination of one for the other - between the "primitive" and the "scholar". The narrative, and its ever-exploding subject matter, shatters this scheme on almost every page. Alexis simply assumes that the human-being is "bad". So, an animal of a special kind. The scholar seeks explanations everywhere. He writes about Buddha and seeks his peace. The whole thing sometimes sounds a bit stereotypical, and sometimes appears that way in the text. The novel was also written in 1943 (*) and surprisingly doesn't seem contaminated by the world-war atmosphere.”

25 years afterwards, I would apply nuances almost everywhere. Today’s readers, in particular the younger ones, may find Kazantzakis’ prose at times too flowery, at times too passionate, too much “given in” to recurrent “Nietzschean Romanticism”. In the year 1943 too many things were at stake in the world, and no one knew what was still to come. You cannot expect anyone, at that time, to remain calm, distant, uninterested.

However, there are moments in which the prose attains peaks of sublime simplicity, transpiring the Cretan landscape.

“The sea, autumn softness, islands bathed in light, a veil of a small, fine rain covering the immortal nudity of Greece. Happy be the man, I thought, whom was given, before dying, to navigate through the Aegean sea. “15

And the following can only be understood, once you have been there:

“This Cretan landscape resembles, so it appeared to me, to the good prose: well articulated, austere, exempt of superficial richness, powerful yet restrained. It expresses the essential with the most simple means.”16

“Suddenly my knees weakened: on the road of the village, under the olive trees, marching at a balanced pace, all red, her black “fichu” over her head, svelte and dashing forward, the widow appeared. Her curved swagger was truly that of a black tigresses, and it seemed to me that a bitter perfume of musk spread itself through the air.”17

For Zorba “defeat” or “failure” is neither the one, not the other. It is simply a signal, an invitation to continue, that the next project, the next voyage are looming in front of us. And they will be a success.

Having lived with this novel, its film, its music, its men and women for more than half-a-century, I cannot but conclude that it remains as one of the most refreshing, stimulating, invigorating European novels of the 20th century. A must for everyone who would love to see “the virginity of the world renewing itself”. And take part in that process.

A sea-water refreshing sunrise, a timely invitation to life, reminding us that “books” are better understood (perhaps even deservedly thrown away) when bathed in grapes, figs, sand, sea and sun.

Berlin, VIII.MM.XX.III.

1French edition, Omnibus, Paris, 1996, including a presentation by Bernard Gestin, “Le chemin escarpé de Nikos Kazantzaki”, page 41. We also revised an English translation, by Carl Wildman. The Greek version of 1968 was consulted many times, to verify the translations. All translations from French and Greek into English are the responsibility of the author of this blog, unless otherwise indicated.

2French 35.

3French 127.

4French, pages 125-26.

5French edition, pg 23. English edition, translated by Carld Wildman.

6French edition, pg. 216. Our translation.

7French edition, back cover.

8French edition, 70.

9French edition , 70.

10French edition, 88.

11Greek 187 French 137 English 127

12French 138-39.

13French 51.

14 Greek page 73, French 51, English 44

15French 20.

16French 34.

17 French 112

--

_beethoven-violin-sonata-no-9-op-47-kreutzer-anne-sophie-mutter-lambert-orkis.jpg)