MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI /JULIO CORTÁZAR: BLOW-UP, OR HOW TO BRIGHTEN THE SUNSHINE WHEN THERE ARE ONLY CLOUDS AROUND.

This contribution is also available as a formatted essay, PDF, at

Let us go back to a cinema hall in the capital of a small South-American republic, probably in 1970. A most cheerful coincidence: the theatre was named “Cine Roma”, on the Street “Colón”, homage to the Italian navigatore and discoverer And it was on a Saturday, afternoon, the invitation having been issued by the “Cinema-Club” Don Bosco, related to the congregation of the “Salesianos”, “The Salesians of Don Bosco”, to assist to the premiere in the country of the film “Blow Up” (USA 1966–UK and Italy 1967), directed by the Italian regisseur Michelangelo Antonioni (*1912 †2007), Carlo di Palma as director of photography. The “Salesians” is a congregation of men in the Catholic Church, founded in 1869 by the Italian priest Saint John Bosco. Taking into account the religious context as such, I presume that most of the “offensive” scenes in the movie had been expurgated, in particular the frolics between the photographer and two too-easy-to-undress young ladies. And that those who were invited to assist to the “restricted” session had been considered as sufficiently “mature”, “responsible”, in spite of their tender age.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The theatre was full. I had to stand, laying my back against the wall separating the first-level of seats from the second one. To my left stood a young woman, of fully Italian descent, studying for her baccalaureate at a religious school. I would meet her again, almost by chance, in the year 2009. I was fascinated by the movie, enjoying my perplexity as I discussed, ex post, with the lady, what possible kind of “meaning” could be attached to such an artistic display. I could not really understand the film then – it would take me 50 years to finally decode it. What I may have said to the young lady in question then shall be better forgotten. Perhaps some silly comparison between “hippies” kicking around London, the destitute sleeping in a “doss house”, and those more “upper-class” getting stoned in a classy villa. Plus a body (apparemment) laying on the ultra-greeny grass of a London park.

Yet the movie left burning (though not unwelcome) traces in my consciousness, and my subconsciousness. Images would reappear, as of sudden. The park, the ladies, the white faces of the mimics, the blurred prints produced by the blow-up hanging on the wall…,

The farthest away was I, then, to just dare imagine the remotest possibility of myself kicking around those very same streets in “Blow-Up”. That remoteness was as strident as my surprise whilst landing in London in June of 1977. To be “reborn” again, much for the better, exhilarated, as Michelangelo Antonioni said when he first came to London, to bathe in that “immense sense of freedom” which burst from every corner of the city. Now also able to watch the uncensored version of the movie.

But it was only between the years 2015-2016 in Berlin when – at last! - my eyes had matured enough to capture all those so-called “tiny details”, which in fact constitute the knots of the Ariadne’s thread, leading you out of the labyrinth appearing on the screen, to the hidden layers of substance – and of artistic meaningfulness. I had by then procured myself new versions of the old copy of 1967. Internet provides us nowadays with a speedy access to interviews, commentaries and articles related to the film, something that in 1970 was impossible. Perhaps some reviews in the newspapers.

Another important factor which explains the reawakening and the enhancement of the film in my heart and mind is a park called “Carl-Ossietzky Park” in Berlin, which as from 2014 became part of my daily routine, passing by two or three times a week, and frequently visited for a gentle stroll, be it winter or summer. That Berliner park resembles to a considerable extent the Maryon Park in London, in particular the front entrance, leading lightly uphill to a green peak surrounded by trees. There is even a sporting area in the back of the park, which one could easily transform in the imagination as the tennis court in which the key final scene of the film takes place. As from my first sighting of the park, I had no doubts: This is my Berliner Maryon Park.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2030m36s%20MARYON%20PARK%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg) |

| Maryon Park, in the film |

|

| Ossietzky Park, Berlin, 2023 |

By no means should be considered secondary: One must read the original short-story by Julio Cortázar, which I hadn’t done before.

Let us, first, just concoct a brief summary of the linear events in the film. A flamboyant, cheeky, dandyish, unscrupulous photographer, Thomas (interpreted by David Hemmings *1941- †2003), comes out of a “doss house” (a night shelter for destitute men), at Consort Road, SE15, where he had camouflaged as a “down and out” lumpen, in order to secretly photograph the misery and hopelessness of people in such a large, rich city. There is here a distinct echo of George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, published in 1933, the first major prosa work of the British author, where he recounts his “voyages” to the lowest level of society, scrambling to eat and to sleep dried and unbothered by fleas, rats and diverse fiendish insects. An attempt by an educated Englishman living on the “sunny side” of the street to better understand those living on the “shadowy” side of the street, as in the case of Thomas.

As

soon as he is out of sight of the his “night-comrades”, he jumps

into a magnificent Rolls-Royce, parked nearby – and drives

to his studio at 39 Princes Place, W11 4QA, where,

priority at the utmost, he must bath and disinfect himself from his

quasi sleepness night at the last prefuge for desesperados.

Not even divine intervention

would have procured me the insight, then, in 1970, that my first

stable abode in London, Bassett Road, 1977-1980, would be

situated at about

a kilometre and a half away, for

me a normal walking distance.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%204m31s.jpg) |

| Notice the meticulous composition in “white” of the image. |

There he will enact with the model Veruschka, Countess von Lehndorff, (Vera Anna Gottliebe Gräfin von Lehndorff), born *1939 in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, then “East-Prussia”, now Russia), one of the iconic scenes of 20th century European movie history, constructing corporeal metaphors regarding Eros’s devotion by a man and a woman

After having exhausted Veruschka, he will tackle a group of models, whom he simply terrorises in order to get his photographic “view-of-the-fashion-world”. Peevish and bored, he leaves the studio and goes to a park, Maryon Park, SE7 8DH, to visit an antique shop. In the park he observes a couple (both man and woman dressed in “greyish colours”) and start taking photos.

The woman, Jane, (interpreted by Vanessa Redgrave, *1937) gets angry and comes to him, “private life should be respected”. She then goes to his studio, under the false assumption he would surrender the negative. By “blowing-up” the print, that is, photographing again and again the “positive”, he believes that something is amiss in one scene, as the very blurred image would suggest a hand pointing with a gun at the couple. He returns to the park (after dismissing two wild young ladies, interpreted by Jane Birkin (*1946-†2023), and Gillian Hills (*1944). One must take into account that by then he must have been very tired, the night at the “doss house” very unlikely to have provided a refreshing sleep (if any at all). He believes that he sees a corpse lying on the green, goes back to the studio, only to find that all negatives and positives, except one very blurred image, have been stolen. On his way to seek help from his editor he sees again Jane queuing in a street, follows her but lands in a rock-and-roll concert where the musicians will get nervous, destroying a guitar and other equipment. But the party attended by his editor is a “dope-party”, everyone “stoned” on marijuana, no understanding or help available. Early next morning he goes back to the park, to find the same group of mimics which appears at the beginning of the film.

The short-story by Julio Cortázar.

Yet a thorough understanding of the cinematographic “backbone” sustaining Blow-Up is to be reached by reading the original short-story by Julio Cortázar (*1914-†1984), “Las Babas del Diablo”, first published in a collection of short-stories entitled “Las Armas Secretas”, in 1959.

Cortázar wrote in “Argentinian”, in a nonchalant, fluid language which goes and comes, repeats itself often, carrying an echo of James’s Joyce stream of consciousness, very much a day-to-day spontaneous way of tackling the world, and this story is essentially a monologue, someone who on a sunny Sunday in Paris (though clouds would systematically appear) felt “terribly happy in that morning”, and adds:

“Among the many ways of combating nothingness, one of the best is to make photos, an activity which should be taught to the children early on, as it requires discipline, aesthetic education, good eyes, and reliable fingers.”1

Soon he would say: “And now a dark cloud passes by…”

Cortázar’s short-story is a literary reflection, bursting with symbolism, of the relationship between fact and fiction, literature and reality. The narrator, the photographer at the Quai de Borbon in Paris, thinks that there is something amiss in the conversation between a woman and a boy, and takes photographs. He then believes that he saw a man, waiting nervously in the car, possibly waiting for the lady to deliver the boy to him. Though the boy runs away. Back in his studio, he blows-up the print obtained from the negative, again and again, trying to establish whether he captured something that did happen indeed, or whether his own eyes were biased, and just imagined something, unverifiable through the photos. It is the last paragraph that contains the key to unveil Antonioni’s architectonic construction of the film as a muted symphony of colours, which are meticulously placed in order to “hint” at the “message” of the film, if a coherent message were to exist.

“Now a big white cloud passes by, like all these days, all this unmeasurable time. What remains to be said is always a cloud, two clouds, or extended hours of a sky perfectly clean, a most pure rectangle nailed with pins against the wall of my room. That’s what I saw when I opened my eyes and dried them up with my fingers: The clean sky, and then a cloud, coming from the left, slowly exhibiting its grace, going away to the right. And then another, though at times everything becomes grey, everything is an enormous cloud,, and as of sudden the splashes of the rain gleam, one could see for a long time rain falling upon the image, like a cry upside down, and, peu à peu the tableau clears itself up, maybe the sun raises, and yet again arrive the clouds, two together, three together. And the pigeons, at times, and one or another sparrow. “2

London as background and subject

We have underlined the phrase “everything becomes grey”. We are in London, 1960s, the “swinging London”, at that time one of the most exciting, innovative cities in the world. A first attempt at de-constructing the movie, so as to construct a “conclusion” (a dangerous word), is that of a portrait of an epoch, the emergence of the Mods, a sort of a juvenile subculture, mostly from working-class and middle-class background, aiming at overcoming those social handicaps through extravagant clothing and behaviour. They appear right at the beginning in the film, stampeding through the streets of London, camouflaged as mimics. Unconventional lifestyles everywhere, be either through liberated sexual modus operandi or the extensive (and intensive) consumption of dope. The contradictions are there, unhidden, no shame to be felt. The photographer who wants to capture (and transmit) the misery of the great city would then jump into his Rolls-Royce and photograph high-fashion models. Those men and women protesting against war and the atomic bomb would then go to a rock-and-roll concert, or similar, to be complemented with heavy drinking and substantial inhaling of cannabis (we assume).

This is also a film about London, but not the London visited by tourists. Apart from the brief apparition of a guard, in red, of the King's Guard, none of the traditional “sight-seeing musts” of London appear, Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey, the Parliament and Big-Ben, Trafalgar Square, Kensington and Hyde Park, not even the River Thames (except for one brief perspective through the window of the villa) seems to have been invited to take part in the procession. It is a secluded, very privatissimo appropriation by Antonioni of London, the city as the mirror of an epoch …, the city as an experimental field for his pictorialist cinema.

The story-telling as such would seem to concentrate on the couple in the park, the photos, the blow-ups, the apparent discovery of a possible murder, a concatenation of events, some of them straight from the short-story by Cortázar. Not quite a thriller, but a thrilling story, to lead, en passant, to the core of the artistic project underpinning the movie: Antonioni is going to “paint” London, facades, streets, stores, cars, gardens, parks, grass, in order to construct his marvellous "own city"… His “own city” is a gigantic fresco ...

Leitfarbe

Let us begin again: This is London, 1960s, as expected, there is a persistent cloudiness across the sky, generating a robust opacity that permeates every corner. It is as if a thin veil of “greyness” has been cast upon the whole scenery. There are few minutes of the entire film in which one could see the resplendent sunrays, mostly reflected on the screen-shield of the Rolls-Royce conducted by the flamboyant, cheeky, dandyish, unscrupulous photographer, (minutes-seconds, 3:51-4:51). The decision to let London appear as a city mostly bathed in greyness it is not aleatory. It may have something to do with the mythicized (slightly unfair) image of London, outside Great Britain, as a place soaked in almost permanent rain and accosted by persistent smog.

That is not the case here. Antonioni’s greyness is his way to set up the framework within which his m metaphors, and parables on the relationship between art and reality, between fiction and facts, between photo and painting, will be acted out.

Yet the sunshine will appear in a rather subtle but systematic way, camouflaged through clothes, cars, dogs, walls and posters. It is an extraordinary achievement, both by Antonioni and Carlo di Palma (*1925-†2004), his camera-director, one of the most remarkable camera-men of the last decades. It is almost as if they were a light-house, camouflaged in the background, very much sotto voce sending those flashes of sunshine, yes, in spite of all the opacity, the greyness, there is still the possibility of light. And of all the other colours. This is cinematographic poetry at its very best, of the highest possible carat, and it is what makes of Blow-Up one of the most beautifully enigmatic, poetical European films of the 20th century.

The use of colours corresponds a little bit to the spirit of a Wagnerian Leitmotiv. Let us decorticate one key scene in the film, the summa summarum of Antonioni’s colour-semantics. Beginning at frame 35:18.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m44s%20B%20RESTAURANT%202%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg) |

| Thomas believes someone is following him. A woman wearing a white raincoat goes away, to the right, and a white car, a “Mini Cooper”, is parked, with all intent, at the corner. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m51s%20RESTAURANT%203%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg) |

| A second woman “in white” appears from the left… |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m56s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg) |

| A third woman, wearing white and a greyish shawl, comes from the right ... |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m49s%20RESTAURANT%207%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg) |

| As Thomas verifies his car, a group of African wearing indigenous attires goes by, to heighten the contrast with the white facade. Notice the “grey” car to the left of the Rolls-Royce. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m39s.jpg) |

| As Thomas tries to follow the man (whom he thinks…) has been following him, a red double-decker appears, then the front of a demonstration for peace and against nuclear weapons. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m40s%20RESTAURANT%208.jpg) |

| As of sudden, a “grey” car will flash by... |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m45s.jpg) |

| Then a “striking” red mini-cooper … |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m47s%20RESTAURANT%209%20ARROW.jpg) |

And to crown it all, a white Volkswagen “beetle” appears to the right…

|

Let us construct our own typology of the functions of colours, to better understand the film. There is a “key-colour”, a Zielfarbe, or Substanzfarbe, in German, which is, of course, Antonioni’s greyness. As defined by the Cambridge Dictionary of English: "The state of the weather when there are a lot of clouds and little light". We then have a Leitfarbe, as a Wagnerian Leitmotiv, which is “white”, as it symbolises the eruption and presence of “sunshine”, in an environment in which because of its opacity is not present. Then we have Nebenfarben, “collateral colours”, basically two: red and then a palette oscillating between lilac, lavender, purple. “Purpleness” is associated with nobility, majesty, imperial … And it is used with intent by Antonioni to label interior scenes, of a particular kind …

|

| Notice the "bleuish" lilla of the shirt worn by Thomas. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2018m47s%20LILA%201.jpg) |

| Shortly afterwards, between Jane Birkin and David Hemmings, the sweater in "purple"... |

|

| Vanessa Redgrave, looking worried, surrounded by “lilla” (lavender). This is the same coloured-environment in which the frolics between the photographer and two young ladies will take place. |

Antonioni is then going to “rubricate” (in the etymological sense of the word, “to paint in red”) the facades of a street, for quite a length, in order to let Thomas drive his Rolls-Royce.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m16s.jpg) |

| One of the very few instances where we see the sun-rays clearly reflected. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m49s.jpg) | ||

| After "red", the car goes back into a "grey" area, puntuctuated by a "white" car and a "white poster", above. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2021m3s.jpg) |

| As the car returns, we see the "white" washing hanging behind, and two men with "white" dogs. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2021m22s.jpg) |

| As Thomas arrives at the "antique-shop", we still see the "white" poster, a little bit of the "white" washing, the two "white" dogs, the two "white" trousers. |

But the sunshine will also be re-born inside, in the interiors. Why not? As there is almost none “outside”, let us just get it “inside”.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2030m49s%20B%20INTERIORS%205.jpg) |

| Thomas arrives, for the second time, to the antique-shop. Notice the "white" trolley carrying the baby. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2031m14s%20INTERIORS%205.jpg) |

| Inside ... |

At night, also the "sunshine" will be re-born...

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2095m44s%20INTERIORS%208.jpg) |

| "Chiarooscuro" with a blonde carrying a "sunray" in her blouse. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m26s%20INTERIORS%209.jpg) |

| "Chiarooscuro" with the publisher, stoned, unable to comprehend the world any more. |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m39s%20INTERIORS%2010.jpg) | ||

| Thomas and his publisher abandon the room, but someone is arriving... |

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m41s%20INTERIORS%2012.jpg) |

| Yes, a splendig sunray "in the middle of the night"... |

You may label it as “pictorial poetry”, you may consider the whole film as a gentle, sedative stroll through a virtual combination of Gli Uffizi of Florence, the Museum of Modern Art of New York and the Tate Gallery of London (Tate I).

The almost perennial clouds exhale a “greyness”

Antonioni’s genial construction is that of using the “greyness” dominating the whole film as a huge, impeccable metaphor of the indecision between accepting reality or self-constructed imagery. Grey is the ocean which can be navigated between two extremes, black (no) and white (yes), with all its tides, fluxes and refluxes. But greyness itself is a “metaphor”, is the veil which hides the possibility of all colours.

Blow-Up was not only Antonioni’s most successful film, commercially. It marked an era, both as portrayer of an epoch, the 1960s, and also as creating, technically, new standards of the highest artistry. A unique combination of poetry, painting, and photography. It also consolidated the career of Vanessa Redgrave, to become later Dame Vanessa Redgrave, DBE, one of the most formidable actresses of the last decades, and a indefatigable fighter for human rights everywhere in the world. It launched the career of Jane Birkin, who died some weeks ago, who was to go to France, becoming partner and muse of Serge Gainsbourg as from 1969, and was to become the “most loved Englishwoman in France”.

Above all, it consolidated the world status of Veruschka, considered by many, then as “the most beautiful woman in the world”, but also, as stated in a German newspaper, “the saddest…”

Veruschka’s father was Heinrich Manfred Ahasverus Adolf Georg Gran von Lehndorff (*1909-†1944), who was executed in 1944 for having taken part in the conspiracy against Hitler. Her mother was sent to a labour-camp, she and the other children were sent first to a children’s home, then retaken by parents, an odyssey that lasted years, fleeing from East Prussia through Germany to arrive in Hamburg, where she would go to school. Carl Ossietzky was a German writer and pacifist, Nobel Peace Prize 1936, arrested in 1933, and died in 1938 in a concentration camp. It is thus that the Ossietzky Park in Berlin, my substitute Maryon Park, is related to Veruschka. And provides a personal, unique perspective.

Masterpieces of "painting" of the 20th century through a camera composition.

In an obituary published in Germany in 2007, Christina Nord said:

“In Blow-Up, the famous film version of a short-story written by Julio Cortázar, Antonioni put simply on stage something which must be considered as a key moment of photography and film-making. “3

"A photogrpaher of the soul", "Fotograf der Seele”, was the comment in Die Chronik des Filmes, Berlin,

1986.We may add: of persons and things, of landscapes and paintings.

In the cover of a DVD edition for the German market, there is a comment by Michael Althen:

“If it is true that the greatness of a regisseur is based on the tenderness which he brings up to the world and the things therein, then the work of Antonioni belongs to the greatest of what the first century of cinema has contributed.”

What else? “Reality versus fiction, or versus the photographic perception (or biased reconstruction) of reality…”

At the same time: “The

negative contains what has been captured by the camera…, the first

“print” (positive) is a positive copy of the negative, but the

next “prints” (blow up) are copies from a … copy. The furthest

the blowing-up continues, the farthest the reality remains.. The more the photo becomes an "abstract painting"...

Also: “A photo is just one way of attempting to capture reality…”, “...of attempting to detain time...”

The mimics, who appear at the beginning, reappear at the end, coming to the park, where Thomas tries to understand what in fact did happen. They will “act” as if tennis balls and rackets were available, inviting Thomas to join the “fictionalised” game. Thomas does accept, “fiction can be understood as real, perhaps rather as an Ersatz des Wirklichen, a substitute of reality”.

The greyness understood as an indecision between “reality” and “fiction”, as an indecision between “yes” and “no”. Thomas remains, so to speak, in the “grey”...

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2085m34s.jpg) |

| Sarah Miles (*1941), appears in a transparent red dress, the only woman in the whole film who wears such an attire, the woman whom Thomas secretly desires, perhaps... |

One could assume that Antonioni took every step available to make the movie as “elusive” as possible, or perhaps rather he displayed his net of symbols (above all colours) as position-lights, so that everyone could risk his own interpretation. But is this a film to be interpreted? One example is the neon sign overlooking the park. What could that possibly mean?

It is important, because in the final scenes, Thomas will look at the sign, as if asking for an answer.

One possible interpretation is as follows:

“The camera's focus has been on Thomas. Now the camera's focus makes a quick shift so it includes the sign, as Thomas turns to look at it. The word in the sign doesn't make sense. Antonioni said he only put up the sign to provide light for the park's night scene and that he didn't want it to make sense to the audience. But I'm just not buying the construction of that huge neon sign only for the purpose of providing light.

One may, however, see in the sign a gun. If the letters are FOA, or FO and an inverted V, then the F is as a gun, the O as a finger on the trigger, and the A or inverted V is the target.”4

But this is a possibility, unverifiable.

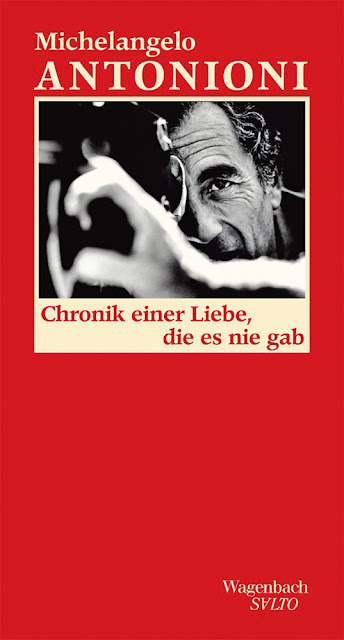

Antonioni was also a writer, at times using his “literary notes” as a way of reflecting back on his films. By chance I stumbled some three years ago onto a carefully edited German version of a collection of short-stories, “Chronik einer Liebe, die es nicht gab” (Chronic of a love which never existed). That is the German title, taken from one of the stories, as the original Italian edition carries “Quel Bowling sul Tevere”, 1983, on the front cover. The English edition added a sub-title “Tales of a Director”.

In one of those stories, the first-person narrator refers to a woman by saying:

“She has a face, which I will never become tired of looking at. Everything in her was worth admiring.”5

The same can be said of Blow-Up: “We will never get tired of watching it, again and again. Everything there is admirable”.

Grazie Mille, Maestro.

Berlin, IX MMXXIII.

1Pg. 2.

2Pg. 7.

3Nachruf, Vollender der Formen. Christina Nord, TAZ, 01.08.2007.

4Juli Kearns, https://idyllopuspress.com/idyllopus/film/bu_5.htm.

5 Chronik einer Liebe, die es nie gab, Wagenbach, 2012, Pg. 97.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%202m16s%20B.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2027m37s%20NBLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2035m18s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN%20ARROWS.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m35s%20RESTAURANT%205%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m44s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m28s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m32s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2093m51s%20INTERIORS%206.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2094m24s%20INTERIORS%207.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2012m20s%20INTERIORS%202.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2077m6s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20104m46s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20106m18s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2077m29s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20101m9s.jpg)