T. S. ELIOT, THE WASTE LAND: “I believe that only the poet can now change the things…”

Video-link:

The French are accused, sometimes and not everywhere, of being too arrogant and of having crowned themselves as the “nation of literature”, la patrie des lettres, par excellence. Yet I owe it to a magnificent French website devoted to literature the privilege of having been alerted to the centenary of The Waste Land, by T.S. Eliot (*1888-†1965), first edition in England, October of 1922, in the publication The Criterion.

Nothing comparable to the pageantry surrounding the first hundred years of “un grand poème unanimement tenu pour un classique moderne et qui ait dominé le XX siècle”1. Indeed, The Waste Land is arguably a milestone of English poetry in the 20th century, both midwife and crowning-jewel of modernism. It remains firmly anchored, even in this epoch of ours (which dislikes poetry so much), in the awareness of readers across the world as one of the indestructible monuments in world literature. Not to be forgotten: On the 2nd of February 1922 Ulysses, by James Joyce, was also published, another monument, to which we hope to return in this blog in a few months.

The voyage through The Waste Land remains a very personal experience. It is a private affair. It would be absurd to repeat herewith even just a portion of the hundreds and hundreds of readings, interpretations, versatile exercises in hermeneutics and exegesis, critical appraisals, as well as the explanations and translations of the many references to other authors, be it from Dante Alighieri to Richard Wagner, from Shakespeare to Baudelaire, from the Romans to the sources in Sanskrit.

At one level The Waste Land is a re-visitation of the pillars of Western culture, but also, to some extent, of Eastern culture, which are being put “back into this life”, that is, the interregnum between the First and the Second World War. Eliot’s poem is largely a “child” of the First World War, of that ominous carnage which destroyed the European belle époque, and created the conditions for the weakening of European world-dominance, thus the emergence of the American empire. And others. It begs for “peace” to be considered as the most valuable asset, as indicated by the words in Sanskrit in the last lines of the poem.

Let such a historical contextualization be reminded, but let us also not allow it to overshadow the recreation of the dreams and fears of the individuals, who perhaps are being let down by history, or simply forgotten. From the high-brow cogitations of the Greeks and Romans we go down to the colloquial and the dialects, the daily kicking-around in London, propelled by the whim of events, which anticipate the arrival of uncontrollable whirlwinds. This is also a poem about London, about that London which has almost disappeared. It is about solitude and “what to do next?”, of avoiding ennui and keep searching for love.

There is a distinctive Englishness in Eliot’s poem (although he was born in the U.S., but naturalised as a British citizen in 1927), yet by that we mean the old Englishness, which now runs the risk of being considered an extinct species. That of being on an island, though by no means an “islander”. Of an Englishman who feels at home being re-born in Italy or in Greece. Even in Germany. Or perhaps it is precisely that “American-Englishness” of him that allowed him to remain, unassumingly, a “citizen of the world”. A very honest author, who never attempted to hide or devalue the decisive role played by Ezra Pound (*1885-†1972) in the construction of the final form of the poem. Ezra Pound, that writer who was generosity in itself, a prodigious poet, who took the risky and perhaps unnecessary decision of getting involved with “politics” – on the wrong side, on top of that.

The Waste Land remains a healing experience, as pertains to someone having been bathed in a pond full of flowers and ashes, full of bones and amiable turtles, still alive, in spite of centuries and centuries, who then emerges out of water to land onto terra, whispering “keep going, keep going…” As someone said to me some time ago, “I read it, but I did not understand it…”. My answer: “This is not a to-be-understood poem, it is a to-be-felt poem…”

It remains also a lighthouse, always beaming yet not blending, whispering cotton-words which have captured the untranslatable experience of every individual, struggling not to lose the compass, still alive today, despite having been conceived in Greek and Latin more than two thousand years ago.

It is as a very private encounter, everyone possessing his or her The Waste Land, each personal parcours remaining unique, yet also universal.

Of course, we need translations, but can The Waste Land really be appreciated, and understood, in any other language but English? Just the title of the poem (which hints doubtless at “infertility”) poses a gigantic challenge to the eventual translator. In French, for example, there are at least three variants, La Terre vaine2 ,Terre inculte, La Terre vague. In German Das wüste Land or Das öde Land, or even more complex, Das brache, öde, wüste Land.

In Spanish, La Tierra Baldía, La Tierra Yerma, La Tierra Agostada, La Tierra Estéril, although the first version seems to remain the “usual” one. In Italian, one approach is La terra desolata.

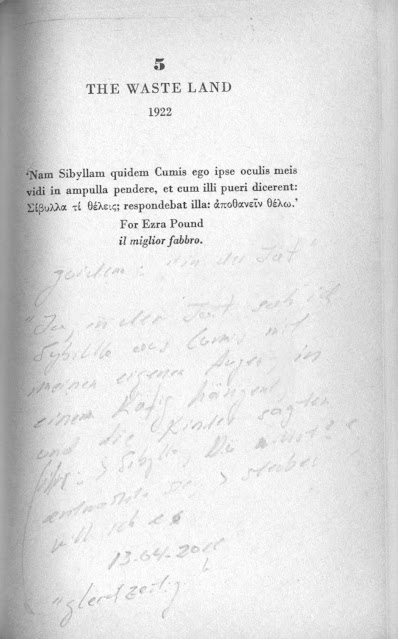

First page of The Waste Land, containing the epigraph and the dedication to Ezra Pound. The text, in Latin and Ancient Greek, comes from chapter 48 of Satyricon, written 62-65 A.D. by Petronius (?- 66 A.D., ordered by Nero to commit suicide)4. This copy belongs to the author. It was bought in London in 1999, as the first copy, bought in London in 1988, was stolen in 1997. The handwritten notes in German were an attempt to produce a German translation of the epigraph, on the 13th of April 2011, and we do hope that they are blurred enough. It is extremely difficult to translate from Latin and Ancient Greek, keeping the melody of the original, as Latin does not have articles, and in Ancient Greek you can conclude phrases without inserting personal pronouns. Hence this possibility in English: “Indeed I myself saw Sibyl of Cumae (with my own eyes), hanging in a jar, and when the boys said, “Sibyl, you desire?”, Sibyl answered, “To die I desire”. The latter sentence in Ancient Greek is simpler: To desire (or “to want”), conjugated in the first-person, to die: Only one word, and the infinitive in Greek is composed of only one word.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Perhaps we can just console all translators by reminding them that, as E.M. Foster said once: “It is just a personal comment on the universe, as individual and as isolated as Shelley's Prometheus”3.

Let us just keep repeating that, notwithstanding its role as lingua mundi, in particular in the globalised business world, one of the most humane reasons to learn English is to be able to read T.S. Eliot in his language.

There is possibly no better indicator of the impact of a literary opus upon its reader than his decision, ex post, to write in the language of that work, which may happen to be not its first. Although I had been aware of the poem decades ago, an intimate get-to-know took place first in London, between 1988 and 1989, “years of transition”, when the author of this blog spent a lot of time kicking around Bloomsbury, yet also doing some relevant work. The Waste Land became an intimate companion, indeed a more relevant one, as the poem seems to supplicate “do not try to understand me”, “just feel me”, “just let me inhabit your dreams, and then you will see…”

What shall I see? Sibyl in a jar, begging for death to arrive, as she has been granted eternal life, but alas not eternal youth…

I shall see the vanity of hoping for eternal youth, realizing that only the “spirit” may survive, if it happens to have been crystallised in words. T.S. Eliot did achieve it.

“I wish I could write English as T.S. Eliot did…”, an impossible task, an unmentionable, even preposterous desire.

The text from line 232 to 248 is recited by Anthony Blanche (Nickolas Grace) in the 1981 film-version of Brideshead Revisited, the novel by Evelyn Waugh. Lines 253 to 256 are the ones most at heart by the writer of these lines.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Anthony Blanche, the flamboyant and Machiavellian cosmopolite in the 1981 TV series of Brideshead Revisited, reciting through a megaphone some lines of The Waste Land, from a balcony in Oxford, to a bemused and spontaneous audience, down on the green.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What about poetry in “our age”? Again, it remains very much a private affair, at one level. At the other, perhaps we should go back to an interview conducted by the French television personality, Bernard Pivot, for its much vaunted literary emission “Apostrophes”, on the 13th of November 1981. The German writer Ernst Jünger (*1895-†1998) was in Paris, partly to celebrate the publication of a new translation of his diaries during the Second World War, the Pariser Tagebuch, Premier Journal Parisien, 1941-43, Second Journal Parisien, 1943-45.

Bernard Pivot was adamantly hostile towards the German writer, trying to corner him down, because of his attempts, as Pivot said, to remain an “aesthete” during those abysmal years. At the end Pivot sort of give in, but only just, quoting the French writer Michel Tournier (*1924-†2016):

“-Est-ce que, Michel Tournier, dans un papier chronique sur vous, il écrit ceci: „Au salut militaire, Jünger préfère le salut par l’écriture ».

-Ah bon…-Vous êtes d’accord avec cette formule ?

-Oui, parfaitement.

-Vous pensez que vous l’avez appliquée tout le temps ?

-J’espère…

-Vous pensez d’ailleurs que c’est le salut par l’écriture, finalement, c’est la seule chose qui importe aux vrais écrivains, non?

-Je crois que le poète est le seul qui peut maintenant changer les choses. »

“I believe that the poet is the only one who can now change the things…”

End of the interview. And of the fruitless assault.

What did Ernst Jünger mean by that phrase? We know that he was a reasonable man, not someone who would assert that changes did not occur, be either through technique, or war, or demographic, political upheavals. He was hinting, in a very elegant way, to the fact that, as nowadays almost everything tends to change, at an ever increasing rate-of-increase, the only possibility of we changing vis-à-vis the world, of we taking distance from the world, and also positioning ourselves into it, is through poetry. If we cannot change “the things”, at least we can change the perception of our way of dealing with “those things”. And perhaps that’s the only thing that matters.

Are we to hope for another T.S. Eliot to appear in the 21st century? If it does, then the chance of survival might increase.

1La République des Lettres, 18.05.2022.

2 La Terre vaine (dans la traduction de Pierre Leyris ou encore Terre inculte dans la version de Pierre Vinclair ou même ailleurs La Terre vague dans celle de Michel Vinaver pour France-Culture) est un poème réputé difficile d’accès, jugé hermétique au premier abord et même aux suivants, truf, La République des Livres, opus cit.

3Forster 1940, pp. 91–92 ▪ Forster, E. M. (1940). "T.S Eliot", pp. 91-92.

4T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land an other poems, faber and faber, London, 1988.

No comments:

Post a Comment