MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI /JULIO CORTÁZAR: BLOW UP, O CÓMO RESCATAR LOS RAYOS DE SOL CUANDO SÓLO HAY NUBES ALREDEDOR.

This contribution is also available as a formatted essay, PDF. at

Una sala de cine en

la capital de una pequeña república sudamericana, probablemente en

1970. La casualidad en su dimensión más

alegre: la sala se llamaba “Cine Roma”, en la calle “Colón”,

homenaje al descubridor italiano. Y era un sábado, a

la tarde, a invitación había sido cursada

por parte del “Cine-Club” Don Bosco, afín a la

congregación de los “Salesianos”, “Los Salesianos de Don

Bosco”, para asistir al estreno en el país de la película “Blow

Up” (Estados Unidos 1966–Reino Unido e Italia 1967), dirigida

por el director italiano Michelangelo Antonioni (*1912 †2007),

Carlo di Palma como director de fotografía. Los “Salesianos”

constituyen una congregación de hombres de

la Iglesia Católica, fundada en 1869 por el sacerdote italiano San

Juan Bosco. Teniendo en cuenta el contexto religioso como tal,

supongo que la mayoría de las escenas “ofensivas” de la película

habían sido expurgadas, en particular las travesuras entre el

fotógrafo y dos jóvenes demasiado fáciles de desnudar. Y que

quienes fueron invitados a asistir a la sesión “restringida”

habían sido considerados suficientemente “maduros”,

“responsables”, a pesar de su tierna edad.

"Que

florezca la mujer más bella del mundo, que se convierta en un sueño

en sí mismo, en un rostro que pueda ser llevado más allá de la

barrera del tiempo..." Thomas (David Hemmings) convence a

Veruschka que deje que el alma y el cuerpo exhuman toda su sustancia,

y todo sus

secretos...

--------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------

-----------------------

El teatro estaba lleno. Tuve que ponerme

de pie, apoyando mi espalda contra la pared que separaba el primer

nivel de asientos del segundo. A mi izquierda estaba una mujer joven,

de ascendencia totalmente italiana, estudiando su bachillerato en una

escuela religiosa. La volvería a encontrar, casi por casualidad, en

el año 2009. Quedé fascinado por la película, disfrutando de mi

perplejidad mientras discutía, ex post, con la señorita,

qué posible tipo de “significado” podría atribuirse a semejante

obra artística. En aquella épocano podía

entender realmente la película; me llevaría 50 años decodificarla.

Entonces será mejor olvidar lo que pude haberle dicho a la joven en

cuestión. Quizás alguna comparación tonta entre los “hippies”

que pasean por Londres, los indigentes que duermen en una “casa de

mala muerte” y los de “clase alta” que se drogan en una

elegante villa . Además de un cuerpo (en

apariencia) tendido sobre el césped ultraverde de un parque

de Londres.

Sin embargo, la película dejó huellas ardientes (aunque no desagradables) en mi conciencia y mi subconsciencia. Las imágenes reaparecerían, de repente. El parque, las damas, las caras blancas de los mímicos, las huellas borrosas que produce la „ampliación“ (blow-up) colgada en la pared…

Muy lejos estaba yo, en aquel entonces, para siquiera atreverme a imaginar la más remota posibilidad de estar dando vueltas por esas mismas calles, en “Blow-Up”. Esa lejanía fue tan estridente como mi sorpresa al aterrizar en Londres en junio de 1977, para “renacer”, a mejor resultado, regocijado, como dijera Michelangelo Antonioni cuando llegó por primera vez a Londres, al bañarme en esa “inmensa sensación de libertad” que brota de cada rincón de la ciudad. Ahora también podría ver la versión sin censura de la película.

Pero no fue hasta los años 2015-2016 en Berlín cuando –¡por fin! - mis ojos habían madurado lo suficiente como para captar todos esos llamados “pequeños detalles”, que en realidad constituyen los nudos del hilo de Ariadna, que llevan fuera del laberinto que aparece en la pantalla, hacia las capas ocultas de sustancia, y de arte. Para entonces ya contaba con nuevas versiones de la antigua copia de 1967. Internet nos proporciona hoy en día un acceso rápido a entrevistas, comentarios y artículos relacionados con la película, algo que en 1970 era imposible. Quizás algunas reseñas en los periódicos.

Otro factor importante que explica el despertar y la intensificación de la película en mi corazón y en mi mente es un parque llamado “Parque Carl-Ossietzky” en Berlín, que a partir de 2014 pasó a formar parte de mi rutina diaria, pasando por allí dos o tres veces por semana. , y visitada con frecuencia para dar un suave paseo, ya sea en invierno o en verano. Este parque berlinés se parece mucho al parque Maryon de Londres, en particular la entrada principal, que conduce ligeramente cuesta arriba hasta una cima verde rodeada de árboles. Incluso hay una terreno deportivo () en la parte trasera del parque, que uno podría fácilmente transformar en la imaginación como la cancha de tenis en la que tiene lugar la escena final clave de la película. Desde que vi el parque por primera vez no tuve dudas: este es mi Maryon Park berlinés.

Maryon Park, en la película

Parque Ossietzky, Berlín, 2023

De ninguna manera debe ser considerado secundario: hay que leer el cuento original de Julio Cortázar, cosa que yo no había hecho antes.

Hagamos primero un breve resumen linear de los eventos de la película. Un fotógrafo extravagante, descarado, dandy y sin escrúpulos, Thomas (interpretado por David Hemmings *1941- †2003), sale de una “doss house” (un refugio nocturno para hombres indigentes), en Consort Road, SE15, donde se había camuflado como un lumpen, “down and out, para fotografiar en secreto la miseria y la desesperanza de la gente en una ciudad tan grande y rica. Hay aquí un claro eco de Down and Out in Paris and London de George Orwell, publicada en 1933, la primera gran obra en prosa del autor británico, donde relata sus “viajes” al nivel más bajo de la sociedad, luchando por comer y dormir, sin ser molestado por pulgas, ratas y diversos insectos diabólicos. Un intento de un inglés educado que vive en el “lado soleado” de la calle de comprender mejor a quienes viven en el lado “oscuro” de la calle, como en el caso de Thomas.

Tan pronto como se pierde de vista de sus

“camaradas de la noche”, se sube a un magnífico Rolls-Royce,

estacionado cerca, y conduce hasta su estudio en 39 Princes Place,

W11 4QA, donde, con máxima prioridad, debe bañarse y

desinfectarse de su (restringido) sueño

nocturno en el último refugio para desesperados. Ni siquiera la

intervención divina me habría permitido saber entonces, en 1970,

que mi primera residencia estable en Londres, Bassett Road,

1977-1980, estaría situada a aproximadamente un kilómetro y medio

de distancia, lo que para mí era una distancia normal a pie.

.

Nótese la meticulosa composición en “blanco” de la imagen.

Allí representará con la modelo Veruschka, la condesa von Lehndorff, (Vera Anna Gottliebe Gräfin von Lehndorff), nacida *1939 en Königsberg (ahora Kaliningrado, luego “Prusia Oriental”, ahora Rusia), una de las escenas icónicas de la historia del cine europeo del siglo XX. Una construcción de metáforas corpóreas sobre la devoción de Eros por un hombre y una mujer.

Después de haber agotado a Veruschka, se enfrentará a un grupo de modelos, a quienes simplemente aterrorizará para obtener su “visión-fotográfica-del-mundo-de-la-moda”. Malhumorado y aburrido, sale del estudio y se dirige a un parque, Maryon Park, SE7 8DH, para visitar una tienda de antigüedades. En el parque observa a una pareja (hombre y mujer vestidos de “colores grisáceos”) y empieza a tomar fotografías.

Nótese la composición del encuadre: “fondo verdoso”, cielo nublado y tanto el hombre como la mujer vestidos con variaciones “grisáceas”. El “gris” allí anticipa que no habrá una respuesta clara a lo que el fotógrafo creía haber capturado.

-----

La mujer, Jane, (interpretada por Vanessa Redgrave, (*1937)

se enoja y le dice: “La vida privada debe ser respetada”. Luego

va a su estudio, bajo la falsa suposición de que él entregaría el

negativo. Al “ampliar” la impresión, es decir, fotografiar una y

otra vez el “positivo”, cree que hay

algo sospechoso en una toma, ya que

la imagen muy borrosa sugeriría una mano apuntando con una pistola a

la pareja. Regresa al parque (después de despedir a dos jovencitas

salvajes, interpretadas por Jane Birkin (*1946-†2023), y Gillian

Hills (*1944).

Hay que tener en cuenta que para entonces ya debía estar muy cansadoEs muy poco probable que la "doss house" le haya proporcionado un sueño reparador (si es que lo hubo). Él cree que ve un cadáver tirado en el césped, regresa al estudio, solo para descubrir que todos los negativos y positivos, excepto uno imagen muy borrosa, han sido robadas. En su camino para pedir ayuda a su editor vuelve a ver a Jane haciendo cola en una calle, la sigue pero aterriza en un concierto de rock and roll donde los músicos se pondrán nerviosos, destrozando una guitarra y otros equipo. Pero la fiesta a la que asiste su editor es una "fiesta de drogas", todos "drogados" con marihuana, no hay comprensión ni ayuda disponible. Temprano a la mañana siguiente, regresa al parque y se encuentra con el mismo grupo de mímicos que aparecen en el comienzo de la película.

El cuento de Julio Cortázar.

Sólo se puede llegar a una comprensión profunda de la “columna vertebral” cinematográfica que sustenta a Blow-Up leyendo el cuento original de Julio Cortázar (*1914-†1984), “Las Babas del Diablo”, publicado por primera vez en una colección de cuentos cortos. titulada “Las Armas Secretas”, en 1959.

Cortázar escrivía en “argentino”, en un lenguaje no pretencioso y fluido que va y viene, se repite a menudo, llevando un eco de la stream of consciousness de James Joyce, en gran medida una forma espontánea del abordar el mundo, día a día,y esa historia es esencialmente un monólogo, alguien que un domingo soleado en París (aunque sistemáticamente aparecieran nubes) se sintió “terriblemente feliz esa mañana”, y agrega:

“Entre las muchas maneras de combatir la nada, una de las mejores es sacar fotografías, actividad

que debería enseñarse tempranamente a los niños, pues exige disciplina, educación estética, buen

ojo y dedos seguros.”1

Pronto diría: “Y ahora pasa una nube oscura…”

El cuento de Cortázar es una reflexión literaria, repleta de simbolismo, de la relación entre realidad y ficción, literatura y realidad. El narrador, el fotógrafo del Quai de Borbon de París, piensa que algo anda mal en la conversación entre una mujer y un niño y toma fotografías. Luego cree que vio a un hombre esperando nerviosamente en el auto, posiblemente esperando que la señora le entregara el niño. Al final el niño huye. De regreso a su estudio, amplia una y otra vez la copia obtenida del negativo, tratando de establecer si capturó algo que realmente sucedió, o si sus propios ojos estaban parcializados, y simplemente imagino algo, incomprobable a través de las fotos.

Es el último párrafo el que contiene la clave para desvelar la construcción arquitectónica de la película por parte de Antonioni como una silenciosa sinfonía de colores, meticulosamente colocados para “insinuar” el “mensaje” de la película, en el caso de que existiera un mensaje coherente. .

“Ahora pasa una gran nube blanca, como todos estos días, todo este tiempo incontable. Lo que queda por decir es siempre una nube, dos nubes, o largas horas de cielo perfectamente limpio, rectángulo purísimo clavado con alfileres en la pared de mi cuarto. Fue lo que vi al abrir los ojos y secármelos con los dedos: el cielo limpio, y después una nube que entraba por la izquierda, paseaba lentamente su gracia y se perdía por la derecha. Y luego otra, y a veces en cambio todo se pone gris, todo es una enorme nube, y de pronto restallan las salpicaduras de la lluvia, largo rato se ve llover sobre la imagen, como un llanto al revés, y poco a poco el cuadro se aclara, quizá sale el sol, y otra vez entran las nubes, de a dos, de a tres. Y las palomas, a veces, y uno que otro gorrión. “2

Hemos subrayado la frase “todo se pone gris”. Estamos en el Londres de los años 60, swinging London, en aquel momento uno de los lugares más apasionantes e innovadores del mundo. Un primer intento de "de-construir" la película, para construir una “conclusión” (una palabra peligrosa), es el de un retrato de una época, el surgimiento de los Mods, una especie de subcultura juvenil, principalmente de trabajadores. de clase media y de clase media, buscando superar esas desventajas sociales mediante vestimenta y comportamiento extravagantes. Aparecen desde el principio de la película, corriendo por las calles de Londres, camuflados como mímicos. Estilos de vida no convencionales en todas partes, ya sea a través del modus operandi sexual liberado o del consumo extensivo (e intensivo) de droga. Las contradicciones están ahí, a corazón abierto: no hay que sentir vergüenza. El fotógrafo que quiere capturar (y transmitir) la miseria de la gran ciudad se subirá a su Rolls-Royce y fotografiará high-fashion modelos. Aquellos hombres y mujeres que protestaban contra la guerra y la bomba atómica irían luego a un concierto de rock and roll, o algo similar, que complementarán con un consumo excesivo de alcohol y una inhalación sustancial de marihuana (suponemos).

Esta es también una película sobre Londres, pero no sobre el Londres visitado por los turistas. Aparte de la breve aparición de un guardia vestido de rojo, King’s Guard, no aparece ninguno de los tradicionales “imprescindibles” de Londres, el Palacio de Buckingham, la Abadía de Westminster, el Parlamento y el Big-Ben, Trafalgar Square, Kensington y Hyde Park, ni siquiera el río Támesis (excepto por una breve perspectiva a través de la ventana de la villa) parece haber sido invitado a participar en la procesión. Es una apropiación a sotto voce, muy privatissimo, por parte de Antonioni de Londres, la ciudad como espejo de una época..., la ciudad como campo experimental para su cine pictorialista.

La narración como tal parecería concentrarse en la pareja en el parque, las fotos, las „ampliaciones” (blow-ups), el aparente descubrimiento de un posible asesinato, una concatenación de acontecimientos, algunos de ellos sacados directamente del cuento de Cortázar. No es exactamente un thriller, sino una historia apasionante, que conduce, de paso, al núcleo del proyecto artístico que sustenta la película: Antonioni va a “pintar” Londres, fachadas, calles, tiendas, coches, jardines, parques, césped, para construir su maravillosa "propia ciudad"... Su "propia ciudad" es un fresco gigantesco...

Leitfarbe

Empecemos de nuevo: esto es el Londres de los años 60. Como

era de esperar, hay una nubosidad persistente en el cielo, generando

una robusta opacidad que impregna cada rincón. Es como si un fino

velo de “gris” hubiera caído sobre todo el paisaje. Son pocos

los minutos de toda la película en los que se pueden ver los

resplandecientes rayos del sol, en su mayor parte reflejados en la

pantalla del Rolls-Royce conducido por el extravagante y

descarado fotógrafo, minutos-segundos, 3:51-4 :51 La decisión

de dejar que Londres aparezca como una ciudad mayormente bañada en

gris no es aleatoria. Puede que tenga algo que ver con la imagen

mitificada (un poco injusta) de Londres, fuera de Gran Bretaña, como

un lugar empapado de lluvias casi permanentes y acosado por un smog

persistente.

Ese no es el caso aquí. El gris de Antonioni es su manera de establecer el marco dentro del cual se representarán sus metáforas, y parábolas, sobre la relación entre arte y realidad, entre ficción y hechos, entre fotografía y pintura.

Sin embargo, la luz del sol aparecerá de una manera bastante sutil pero sistemática, camuflada a través de ropas, coches, perros, paredes y carteles. Es un logro extraordinario, tanto de Antonioni como de Carlo di Palma (*1925-†2004), su director de cámara, uno de los camarógrafos más notables de las últimas décadas. Es casi como si existiera un faro, camuflado en el fondo, muy a sotto voce enviando esos destellos de sol, sí, a pesar de toda la opacidad, el gris, todavía existe la posibilidad de que haya luz. Y de todos los demás colores. Se trata de poesía cinematográfica en su máxima expresión, del mayor quilate posible, y es lo que hace de Blow-Up una de las películas europeas más bellamente enigmáticas y poéticas del siglo XX.

El uso de los colores corresponde un poco al espíritu de un Leitmotiv wagneriano. Concentrémonos en una escena clave de la película, el summa summarum de la semántica del color de Antonioni. A partir del fotograma 35:18.

Thomas, vestido con pantalones blancos, llega a un restaurante para encontrarse con su editor. La fachada fue pintada de “blanco” por instrucción de Antonioni, al igual que el las alas de madera de la ventana “grisácea". Pasa una señora con falda gris y blusa blanca, en la esquina se coloca con toda intención semántica un auto “gris oscuro”.

Thomas cree que alguien lo está siguiendo.

Una mujer con un impermeable blanco se aleja, a la derecha, y un

coche blanco, un “Mini Cooper”, está aparcado, con toda

intención, en la esquina.

Una segunda mujer

“vestida de blanco” aparece desde la izquierda…

Una tercera mujer, vestida de blanco y con un chal

grisáceo, viene por la derecha…

Mientras un hombre parece huir de la ventana,

aparece una cuarta mujer, blanca y gris, quizás la misma que en el

cuadro inicial. La fachada del otro lado de la calle también fue

pintada de blanco, siguiendo instrucciones de Antonioni.

Cuando Thomas sale a investigar, aparece una mujer toda

vestida de blanco (excepto su bolso), como un impecable rayo de sol,

recién aterrizado del cielo. Nótese que

el color de todos los coches no difiere mucho del “gris azulado”

del asfalto.

Mientras Thomas revisa su auto, pasa un grupo de

africanos vestidos con atuendos indígenas, para realzar el contraste

con la fachada blanca. Obsérvese el auto

"gris" a la izquierda del Rolls-Royce.

Mientras Thomas intenta seguir al hombre (que

cree…, que lo ha estado siguiendo), aparece un bus

rojo de dos pisos y luego el frente de una manifestación por la paz

y contra las armas nucleares.

De repente, un

coche “gris” pasará rápidamente…

Luego un “llamativo” mini-cooper rojo…

Y para coronar todo un

Volkswagen “escarabajo” blanco aparece a la derecha…

Construyamos nuestra propia tipología de las funciones de los

colores, para comprender mejor la película. Hay un “color clave”,

un Zielfarbe, o Substanzfarbe, en alemán, que es, por

supuesto, el gris de Antonioni. Según lo define el Diccionario

Cambridge de inglés: "El estado del tiempo cuando hay

muchas nubes y poca luz". Tenemos entonces un Leitfarbe

(color „líder”), a modo de Leitmotiv

wagneriano, que es “blanco”, ya que simboliza la erupción y

presencia del “sol”, en un entorno en el que, por la

opacidad, no está presente. Luego tenemos Nebenfarben,

“colores colaterales”, básicamente dos: el rojo y luego una

paleta que oscila entre lila, lavanda y púrpura.

El “púrpura” se asocia con la nobleza, la majestad, lo imperial…

Y Antonioni lo utiliza intencionadamente para etiquetar escenas

interiores, de un tipo particular…

Obsérvese

el lila "azul" de la camisa que

usa Thomas.

Poco después, entre Jane Birkin y David Hemmings, el

suéter en "púrpura"…

Vanessa Redgrave, luciendo preocupada, rodeada de “lila”

(lavanda). Este es el mismo ambiente coloreado en el que tendrán

lugar los juegos entre el fotógrafo y las dos

jóvenes.

Antonioni va comienza

a “rubricar” (en el sentido etimológico de la palabra, “pintar

de rojo”) las fachadas de una calle, durante bastante tiempo, para

dejar que Thomas conduzca su Rolls-Royce.

Uno

de los pocos instantes en los que vemos los

rayos del sol claramente reflejados.

Después del "rojo", el coche

vuelve a una zona "gris", marcada por un coche "blanco"

y un "póster blanco", arriba.

Cuando

el coche retrocede, vemos la ropa "blanca" colgada detrás

y dos hombres con perros "blancos".

Cuando

Thomas llega a la "tienda de antigüedades", todavía vemos

el cartel "blanco", un poco de la ropa "blanca",

los dos perros "blancos", los dos pantalones

"blancos".

Pero el sol también renacerá en el

interior, en los interiores. ¿Por qué no? Como casi no hay nada

“afuera”, dejémoslo “adentro”.

Thomas llega, por

segunda vez, a la tienda de antigüedades. Obsérvese

el carrito "blanco" que lleva al bebé.

Por la noche, también renacerá el

"sol"...

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2094m24s%20INTERIORS%207.jpg)

Claro-oscuro"

con una rubia que lleva un "rayo de sol" en la

blusa.

"Claro-oscuro" con el editor,

drogado, incapaz de comprender más el mundo.

Thomas

y su editor abandonan la habitación, pero alguien llega...

Sí,

un espléndido rayo de sol "en medio de la noche"...

Se

puede etiquetarla como “poesía pictórica”, se

puede considerar toda la película como un paseo suave y

sedante a través de una combinación virtual de los Gli Uffizi

de Florencia, el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York y la Tate

Gallery de Londres. (Tate I).

Las nubes casi perennes exhalan un “gris”

La genial construcción de Antonioni consiste en utilizar el “gris” que impera en toda la película como una enorme e impecable metáfora de la indecisión entre aceptar la realidad o las imágenes autoconstruidas. El gris es el océano que se puede navegar entre dos extremos, el negro (no) y el blanco (sí), con todas sus mareas, flujos y reflujos. Pero el gris en sí es una “metáfora”, es el velo que oculta la posibilidad de todos los colores.

Blow-Up no sólo fue la película de mayor éxito comercial de Antonioni, sino que marcó una época, tanto como retrato de una época, la década de 1960, como también como creación de nuevos estándares, técnica y artísticamente. Una combinación única de poesía, pintura y fotografía.

También consolidó la carrera de Vanessa Redgrave, para convertirse

más tarde en Dame Vanessa Redgrave, DBE, una de las actrices

más formidables de las últimas décadas y una luchadora infatigable

por los derechos humanos en todo el mundo. Lanzó la carrera de Jane

Birkin, fallecida hace algunas semanas, que se fue a Francia, se

convirtió en socia y musa de Serge Gainsbourg a partir de 1969, y se

transformó en la “inglesa más querida

de Francia”.

Sobre todo, consolidó el estatus mundial de

Veruschka, considerada por muchos entonces como “la mujer más

bella del mundo”, pero también, como afirma un periódico alemán,

“la más triste…”

El padre de Veruschka

fue Heinrich Manfred Ahasverus Adolf Georg Gran von Lehndorff

(*1909-†1944), quien fue ejecutado en 1944 por haber participado en

la conspiración contra Hitler. Su madre fue enviada a un campo de

trabajo, ella y los demás niños fueron enviados primero a un hogar

infantil, luego retomados por parientes,

una odisea que duró años, huyendo de Prusia Oriental a través de

Alemania para llegar a Hamburgo, donde iría a escuela. Carl

Ossietzky fue un escritor y pacifista alemán, premio Nobel de la Paz

en 1936, arrestado en 1933 y muerto en 1938 en un campo de

concentración. Por eso el parque Ossietzky de Berlín, mi sustituto

del parque Maryon, está relacionado con Veruschka. Y

proporciona una perspectiva personal y única.

Obras maestras de la "pintura" del siglo XX a

través de una composición de cámara.

Cuadro a

12m20s, “Una Obra de Arte”. La recreación de Antonioni (y di

Palma) del claroscuro de Caravaggio. Obsérvese

el pantalón blanco de Thomas, el suéter blanco de su asistente, así

como las rayas blancas en el vestido de la mujer de la izquierda y el

atuendo gris plateado de la mujer de la derecha.

Otra

“Obra de Arte”, “claroscuros” transportados a la noche, con

algunas alusiones a Rothko, las fachadas blancas y rojas fueron

pintadas bajo las instrucciones de Antonioni, que no estaban allí,

cerca de la tienda de antigüedades de la esquina, bajo la luz del

día. . 77:06

En un obituario publicado en Alemania en

2007, Christina Nord dijo:

“En Blow-Up, la famosa versión cinematográfica de un cuento escrito por Julio Cortázar, Antonioni puso simplemente en escena algo que debe considerarse como un momento clave de la fotografía y la realización cinematográfica. “3

"Un fotógrafo del alma", "Fotograf der Seele", fue el comentario en Die Chronik des Filmes, Berlín, 1986. Podemos agregar: de personas y cosas, de paisajes y pinturas.

En la portada de una edición en DVD para el mercado alemán hay un comentario de Michael Althen:

“Si es cierto que la grandeza de un director se basa en la ternura que aporta al mundo y a las cosas que en él se encuentran, entonces la obra de Antonioni pertenece a lo más grande que ha aportado el primer siglo del cine”.

¿Qué otra cosa? “Realidad versus ficción, o versus

percepción fotográfica (o reconstrucción sesgada) de la realidad…”

Al mismo tiempo: “El negativo contiene lo que ha sido captado por la cámara…, la primera “huella” (positivo) es una copia positiva del negativo, pero las siguientes “huellas” (ampliadas) son copias.

Los mímicos que aparecen al principio reaparecen al final, llegando al parque, donde Thomas intenta comprender qué sucedió realmente. Ellos “actuarán” como si tuvieran a su disposición una pelota de tenis y raquetas, invitando también a Thomas a unirse al juego “ficticio”. Thomas acepta que “la ficción puede entenderse como real, quizás más bien como un Ersatz des Wirklichen, un sustituto de la realidad”.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20104m46s.jpg)

El gris entendido como una

indecisión entre “realidad” y “ficción”, como una

indecisión entre “sí” y “no”. Thomas

permanece, por así decirlo, en el “gris”…

Toma final: Thomas, solo con su

cámara, en el green. El cotizado y casi idolatrado fotógrafo de

moda es incapaz de decidir si lo que vio en ese mismo verde fue real,

o si fue sólo una construcción de su imaginación, reverberada por

la cámara.

Sarah Miles (*1941), aparece con un vestido

rojo transparente, la única mujer en toda la película que viste tal

atuendo, la mujer que Thomas desea en secreto, tal vez…

Se podría suponer que Antonioni tomó todas las medidas

posibles para hacer la película lo más “escurridiza” posible, o

tal vez más bien mostró su red de símbolos (sobre todo colores)

como luces de posición, para que cada uno pudiera arriesgar su

propia interpretación. ¿Pero es ésta una película para ser

interpretada? Un ejemplo es el letrero de neón que domina el parque.

Que podría significar eso?

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2077m29s.jpg)

Es importante,

porque en las escenas finales, Thomas mirará el cartel, como

pidiendo una respuesta.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20101m9s.jpg)

Una

posible interpretación es la siguiente:

“El enfoque de la cámara ha estado en Thomas. Ahora el

enfoque de la cámara hace un cambio rápido para incluir el letrero,

mientras Thomas se gira para mirarlo. La palabra en el cartel no

tiene sentido. Antonioni dijo que sólo colocó el letrero para

iluminar la escena nocturna del parque y que no quería que tuviera

sentido para la audiencia. Pero no voy a comprar la construcción de

ese enorme letrero de neón sólo con el fin de proporcionar luz.

Sin

embargo, en el cartel se puede ver un arma. Si las letras son FOA, o

FO y una V invertida, entonces la F es un arma, la O es un dedo en el

gatillo y la A o V invertida es el objetivo”.4

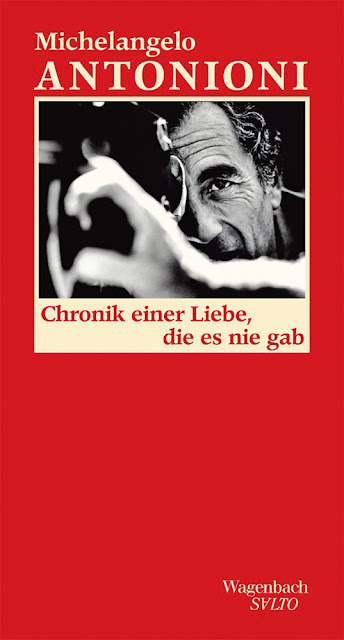

Antonioni también fue escritor y en ocasiones utilizó sus “notas literarias” como una forma de reflexionar sobre sus películas. Por casualidad me topé hace unos tres años con una versión alemana cuidadosamente editada de una colección de cuentos, “Chronik einer Liebe, die es nicht gab” (Crónica de un amor que nunca existió). Éste es el título alemán, tomado de uno de los cuentos, ya que la edición original italiana lleva en la portada “Quel Bowling sul Tevere”, 1983. La edición en inglés añadió un subtítulo “Cuentos de un director”.

En uno de esos cuentos, el narrador en primera persona se

refiere a una mujer diciendo:

“Tiene una cara que nunca me cansaré de mirar. Todo en ella era digno de admirar.”5

Lo mismo puede decirse de Blow-Up: “Nunca nos cansaremos de verlo una y otra vez. Todo allí es admirable”.

Grazie Mille, maestro.

Berlín, IX MMXXIII.

1

pág. 2.

2 pág. 7.

3Nachruf, Vollender der Formen. Christina Nord, TAZ, 01.08.2007.

4Juli Kearns, https://idyllopuspress.com/idyllopus/film/bu_5.htm.

5 Chronik einer Liebe, die es nie gab, Wagenbach, 2012, pág. 97.

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2030m36s%20MARYON%20PARK%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%202m16s%20B.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%204m31s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2027m37s%20NBLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2035m18s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN%20ARROWS.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m44s%20B%20RESTAURANT%202%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m51s%20RESTAURANT%203%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2036m56s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m35s%20RESTAURANT%205%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m44s%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2037m49s%20RESTAURANT%207%20BLOG%20JC%20HERKEN.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m39s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m40s%20RESTAURANT%208.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m45s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2038m47s%20RESTAURANT%209%20ARROW.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2018m47s%20LILA%201.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m16s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m28s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m32s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2020m49s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2021m3s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2021m22s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2030m49s%20B%20INTERIORS%205.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2031m14s%20INTERIORS%205.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2093m51s%20INTERIORS%206.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2095m44s%20INTERIORS%208.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m26s%20INTERIORS%209.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2012m20s%20INTERIORS%202.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2077m6s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%20106m18s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2085m34s.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m39s%20INTERIORS%2010.jpg)

%202-1%20-%20frame%20at%2097m41s%20INTERIORS%2012.jpg)