HENRY MILLER, TROPIC OF CANCER: A PLEA FOR SYSTEMATIC INSOUCIANCE.

There are two writers responsible for the first-apparition of Henry Miller (*1891-†1980) in this blog–planned as such, yet not this early. The first one is the French Albert Camus (*1913-†1960). The second one is the British George Orwell (Eric Blair) (*1903-†1950).

End of 1990, London. The writer of these lines was preparing to leave the English capital and settle in Paris, France. He was hence doing his utmost to improve his French, and one of the resources he had at hand were the books by Albert Camus, in particular his novels, which he had read decades ago, first in Spanish and then end of the 1980s in French. It was not only “L’Étranger” (1942), but his relatively lesser-known works like “La Peste” (1947) and “La Chute” (1956). Both leave a bitter after-taste, plunging the reader into a somehow gloomy and disenchanted mood. One tends to feel sort of “out of spirits”1.

To counter that creeping Camusian existentialist “Angst”, we ploughed through our reservoir of books, and stumbled onto “Tropic of Cancer”, by Henry Miller, the novel published in Paris in 1934 which made him universally famous, but also a proscribed writer in most countries until the early 1960s. As soon as the first pages settled down, we started to feel much, much better. It begins as follows:

“I am living at the Villa Borghese. There is not a crumb of dirt anywhere, nor a chair misplaced. We are all alone here and we are dead. (…) It is now the fall of my second year in Paris. I was sent here for a reason I have not yet been able to fathom.

I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.”2

|

Early 2022, Berlin, Germany. Saint John (Sankt Johannis) tends to favour the writer of these lines with special indulgence and condescension. On a sunny day we found on a pew outside one of the churches devoted to the Evangelist a 1957 Penguin Books edition of “George Orwell. Selected Essays”. Most of the essays included in that antique-copy were unknown to us, and the title of the first and the longest one of those pieces of writing was enigmatic enough: “Inside the Whale”3.

We began reading it‒and could not stop until the last page had been reached. And we would revisit it, again, and again. Perhaps one of the best essays ever written by Orwell, no doubt the most readable and enjoyable. It is centred on the novelistic work by Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer (1934), Tropic of Capricorn (1939), Black Spring (1936 ), though with a special emphasis on the first novel. Yet it is also a panoramic appraisal of English (and European) literature in the first four decades of the 20th century. And an incisive and humorous portrayal of those writers who would canalize the mainstreams due to shape the whole of the 20th century – and our epoch as well: James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Louis Ferdinand Céline and Henry Miller.

By the late 1930s, early1940s George Orwell had become an uncompromising anticommunist, and a fierce adversary of those English Marxists trying to consolidate a partisan narrative giving priority to the “class struggle”. Orwell’s attitude at the time was rooted, at least partially, in his own experience of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), where he was injured, and was appalled by the fact that Communists, Trotskyists and Anarchists were keener in neutralising themselves within the “Republican Front”, rather than combating the Nacionales, on the other side. Henry Miller did warn him in Paris, where the English writer met the American author for the first time, before joining the rank of the Republicanos.:

“I first met Miller at the end of 1936, when I was passing through Paris on my way to Spain. What most intrigued me about him was to find that he felt no interest in the Spanish war whatever, He merely told me in forcible terms that to go to Spain at that moment was the act of an idiot. He could understand anyone going there from purely selfish motives, out of curiosity, for instance, but to mix oneself up in such things from a sense of obligation was sheer stupidity.”4

Orwell thought, at first, that Miller’s attitude then was simply “irresponsible”, as totalitarianism was consolidating itself in Germany and Italy, concentration camps and ethnic persecutions becoming a feature of daily life. We will come back to Miller’s view-of-the-world, to his life and writing constituting, as we understand it, “a plea for systematic insouciance”. Such an attitude, however, should not be equated to “indifference”, but let us concentrate on the prose, on that prose which Orwell praised, once and again:

“Here in my opinion is the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English races for some years past. Even if that is objected to as an overstatement, it will probably be admitted that Miller is a writer out of the ordinary, worth more than a single glance; and after all, he is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses. ”5

|

| Copy of the 1957 edition found by the author of the blog in the Saint John Church in Berlin |

Tropic of Cancer was soon proscribed in most countries, except France, as being an “indecent” novel overflowed by a “filthy language”. There is peradventure an unnecessary repetition of **** words, mostly generated by the daily intercourse and the paraphernalia associated with the “industry-of-the-flesh” in France, in those years one of the main tourist attractions of the country. That “industry”, be either at the street level, or at the one of the maisons closes, or at the aristocratic milieu (please consult the relevant pages of À la recherche du temps perdu by Marcel Proust), was engineered by “genuine” labourers and clients. Not quite the same as with that other “tourist industry”, “painting”, as Orwell described it:

“It has been reckoned that in the late twenties there were as many as 30,000 painters in Paris, most of them impostors.”6

As Orwell said, one is resolute not to let the “filth” (if such were to be the case) “impress” us. It is sort of annoying, perhaps at the beginning, but then it ceases to matter, almost as if those words and phrases had become mosquitoes incapable of stinging, whose buzz becomes more and more inaudible, until we do not notice them, albeit they might still be kicking around. Such a metamorphosis is not casual. It is the magic of Miller’s prose, of one of those rare writers who can transform the austerest room in the shabbiest hotel in Paris into an oasis populated by honeyed-dreams, letting both body and soul be soothed by the irrefutability of the present and the dream of writing that novel.

Tropic of Cancer is, at one level, an autobiographical novel, of an American writer begging Paris to help him exorcise himself through a novel “whose kind has never been seen before”. To a large extent it is also a novel about Paris in itself, above all about one American in Paris, but taking place not during the “roaring twenties”, rather in the early thirties, when the dark clouds of recession and Fascism were hovering above:

“...the American dead-beats cadging drinks in the Latin Quarter”7.

We are thus invited to jump into the carrousel of “dead-beats”, would-be artists, amateur-philosophers, refugees, prostitutes, flesh-obsessed males and females (who do not have to fall into the former category) but also men and women who, in their broken and aimless way, are looking for love, or at least for some suitable Ersatz. Some are deluded by a mysterious voice which whispered into their ears, “there is something there in Paris, that must be found...”

But it is also the plea of a free man:

“….My eye, but I’ve been all over that ground – years and years ago. I’ve lived out my melancholy youth, I don’t give a fuck any more what’s behind me, or what’s ahead of me. I am healthy. Incurably healthy. No sorrows, no regrets. No past, no future. The present is enough for me. Day by day. Today! Le bel aujourd’hui!”8

Few (even those reluctant to stomach the “filth”) would not fail to be seduced by that rhythm-blessed prosateur, whose lines emulate the waves and the stillness of the river Seine. We would soon discover where the source for that balsamic flow of words come from, and it had to be a great poet:

“...we used to spend whole evenings discussing the relatives virtues of Paris and New York. And inevitably there always crept into our discussions the figure of Whitman, that one lone figure which America has produced in the course of her brief life. In Whitman the whole American scene comes to life, her past and her future, her birth and her death. Whatever there is of value in America Whitman has expressed, and there is nothing more to be said. The future belongs to the machine, to the robots. He was the poet of the Body and the Soul, Whitman. The first and the last poet. He is almost undecipherable today, a monument covered with rude hieroglyphs for which there is no key. It seems strange almost to mention his name over here. There is no equivalent in the languages of Europe for the spirit which he immortalised. Europe is saturated with art and his soil is full of dead bones and her museums are bursting with plundered treasures, but what Europe has never had is a free, healthy spirit, what you might call a MAN. Goethe was the nearest approach, but Goethe was a stuffed shirt, by comparison. Goethe was a respectable citizen, a pedant, a bore, a universal spirit but stamped with the German trade-mark, the double eagle. The serenity of Goethe, the calm, Olympian attitude, is nothing more than the drowsy stupor of a German bourgeois deity. Goethe is an end of something, Whitman is a beginning.”9

Miller’s Tropic of Cancer has been placed, together with James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Louis-Ferdinand Celine’s Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932), as the three innovative thunderbolts illuminating the landscape of world literature in the first-half of the 20th century, leaving unerasable traces, right up to now. Yet although they share to some extent that “dragging of the “real-politik” (should actually be “Realpolitik”) of the inner-mind” into the open”10, they respond to different motivations and seek different end-stations.

Joyce’s Ulysses, perhaps the most pertinent (and longest) novel on banalities ever written, is the splendid firework of a poet who was adamant he had to transform the standard language, in order to create his “own”. That, at least for him, the only possibility of enhancing literature as a consolation of life was through letting the “stream of consciousness” impose its own world, its own hieroglyphs, its “never-quite-to-be-satisfactorily-answered” questions. Just let it flow...

Henry Miller had no intention to impress anyone, much less to claim new aesthetics heights. Let alone to tell the world what should be done to stop sauvage capitalism destroying the earth. Céline’s Voyage au bout de la nuit is, indeed, the voyage of an angry young Frenchman through Europe, America and Africa, after having been horrified by the First World War, trying to make sense of the absurdity of the world, the continuous exploitation of men by other men. A nihilistic (perhaps) roar, exhuming anti-nationalism, anti-capitalism, anti-colonialism, crystallised through a revolutionary use of the spoken language and argot, written by a trained, doctored surgeon, who made the costless medical service to the poor and the forlorn outsiders one of the moral imperatives of his life. Yet there is anger in Celine, a resolute rejection of any type of “idealism”. That kind of “amoral” moral message may carry seeds, capable of germinating dangerous ethnic prejudices.

Henry Miller was only interested in finding himself as a writer, in letting the embryonic writer within himself burst into the open, taking possession of the person. He thought he could achieve that goal only in Paris‒and he was right.

One is even tempted to suggest that there is a pre-conceived gusto to embark on the “shadowy” side of the street, in order to let the “sunny” side gleam even “sunnier”. Here follows the description of some streets of Montmartre, one of his (and his acquaintances) “hunting ground” for sexual thrill and eventual one-night stands:

“And I know what a devil’s street is the Faubourg Montmartre with its brass plates and its rubber goods, the lights twinkling all night and sex running through the street like a sewer. To walk from the Rue Lafayette to the boulevard is like running the gauntlet; they attach to you like barnacles, they eat into you like ants, they coax, wheedle, cajole, implore, beseech, they try it out in German, English, Spanish, they show you their torn hearts and their busted shoes, and long after you have chopped the tentacles away, long after the fizz and sizzle has died out, the fragrance of the lavabo clings to your nostrils‒it is the odour of the Parfum de Dance, whose effectiveness is guaranteed only for a distance of twenty centimetres. One could piss away a whole lifetime in that little stretch between the boulevard and the Rue Lafayette. Every bar is alive, throbbing, the dice loaded, the cashiers are perched like vultures on their high stools and the money they handle has a human stink to it.”11

But then, he abandons “that world” and enters into the one he really cares most for:

“It is only later, in the afternoon, when I find myself in an art gallery on the Rue de Sèze, surrounded by the men and women of Matisse, that I am drawn back again to the proper precincts of the human world. On the threshold of that big hall whose walls are now ablaze, I pause a moment to recover from the shock which one experiences when the habitual gray of the world is rent asunder and the color of life splashes forth in song and poem. I find myself in a world so complete, so natural, that I am lost. I have the sensation of being immersed in the very plexus of life, focal from whatever place, position or attitude I take my stance. Lost at when once I sank into the quick of a budding grove and seated in the dining room of that enormous world of Balbec. I caught for the first time the profound meaning of those interior stills which manifest their presence through the exorcism of sight and touch. Standing on the threshold of that world which Matisse has created I re-experienced the power of that revelation which had permitted Proust to so deform the picture of life that only those who, like himself, are sensible to the alchemy of sound and sense, are capable of transforming the negative reality of life into the substantial and significant outlines of art.”12

Tropic of Cancer should be read while enjoying the company of The Colossus of Maroussi (1941), considered by many and himself as his best opus, his account of the sojourn in Greece, following an invitation of Lawrence Durrell (*1912-†1990) who, de facto, had made Corfu his home. This journey took place in 1939, a last European exploration, aware of the inevitable return to the States, as the signs indicated that the Ides of Mars (Idus Martiae) were soon to impose their own calender of slaughter and terror. The “Colossus” as such is George Katsimbalis (*1899-†1978), a Greek poet who acts both as a core-reference for Miller of what a man of letters should be, and who also guides Miller into the Greece of always, that of then, and perhaps also that of the future.

|

| Copy bought in Paris in 1998, and read during a two-week sojourn in Crete, Greece, in the same year |

It is, at a first level, a charming and seducing portrait of a man discovering Greece almost like a child being confronted for the first time with kilos of chocolate ice. He was not a tourist, he was a voyageur intent to rescue the hidden layers of that ever-being-reborn Greek past, and mixing them within his soul. He came not to “discover”, but to “mix-in”:

“At Marseille I took the boat to Piraeus. My friend Lawrence was to meet me in Athens and take me to Corfu. (…) The voyage lasted four or five days, , giving me ample time to make acquaintance with those whom I was eager to know more about. Quite by accident the first friend I made was a Greek medical student returning from Paris. We spoke French together. The first evening we talked until three or four in the morning, mostly about Knut Hansum ( ), whom I discovered the Greeks were passionate about. It seemed strange at first to be talking about this genius of the North while sailing into warm waters. But that conversation taught me immediately that the Greeks are an enthusiastic, curious-minded, passionate people. Passion – it was something I had long missed in France.”13

And so it would continue – Henry Miller in a state of ecstatic trance, getting drunk both by wine and the Greek light, converting encounters with poets, store-keepers, navigators, thieves, drunkards, beggars, dogs, statues, columns, stones and trees, and even garbage, into rendezvous with the highest, and the lowest, of the Greek Gods. “I am searching for the divine…”, he said. And he found it.

“The greatest single impression which Greece made upon me is that it is a man-sized world. It is true that France also conveys that impression, and yet there is a difference, a difference which is profound. Greece is the house of the gods, they may have died, but their presence still makes itself felt. The gods were of human proportion: they were created out of the human spirit. In France, as elsewhere in the Western world, this link between the human and the divine is broken.”14

No one who landed for the first time in Corfu or Crete could fail to recognize the sensations, and the unasked-for joy so magnificently described by Miller:

“The light of Greece opened my eyes, penetrated my pores, expanded my whole being. (…) Greece herself may become embroiled, as we ourselves are becoming embroiled, but I refuse categorically to become anything less than the citizen of the world which I silently declared myself to be when I stood in Agamemnon’s tomb. From that day forth my life was dedicated to the recovery of the divinity of man.”15

“The Colossus...” is a book written by a Romantic writer – yes, Henry Miller was a Romantic writer, in the best German tradition of the term. That has perhaps a little to do with the fact that his parents were German, that he spoke some German, and had read avidly most of the classics in German literature. Much more with that Americanness injected by Ralph Waldo Emerson (the epigraph in Tropic of Cancer comes from him) and Henry David Thoreau, who already beg for a return to nature in order to escape from the crushing industrialization swamping more and more corners of the world.

He is a Romantic writer, in spite of a written language which at times exhales too many ****word, in the sense of letting those “invisible forces” and “divinities” back-boiling in nature, buildings and people be recreated, made “visible”, through his writing. A Whitmanian romantic, perhaps also a proletarian and somehow reckless Nietzchean16, not dodging the dirt, or what most people would categorize as such, rather believing that it is there where the hidden, new beauty would emerge.

Miller’s prosa work, liberating language, letting the Realpolitik of the inner mind and of the Ero’s jungle deep inside the soul go rampant into the open, par chance also becoming quelque fois poetry, is one of the most influential of the 20th century. Needles to mention here the dozens and dozens of American (but not only…) writers who have acknowledged his heritage, his impetus, his bursting, unrestrained, creative writing signalling the wide-spread fields, waiting to be explored by men and women who have no fear of being reborn, naked and avid, of simply allowing their souls to scream and cry, indifferent to the echoes which may emerge ex post.

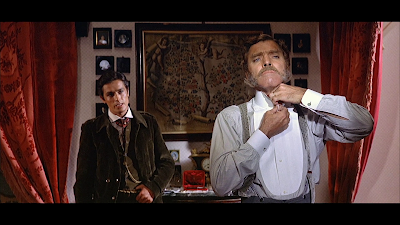

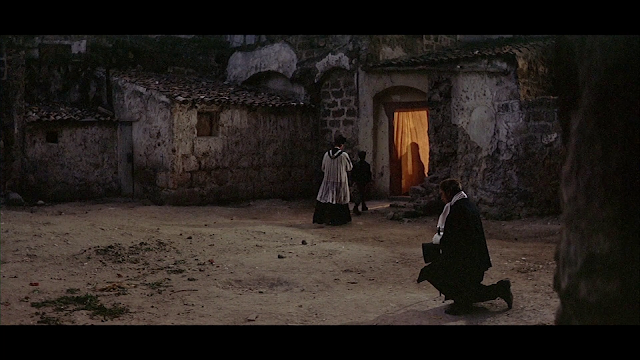

It is by certain not a coincidence that the only book to appear (fully) in one of the best, and more relevant, films of the 20th century, Apocalypse Now (1979), produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, is Henry Miller’s Sexus, 1949, (first book of The Rosy Crucifixion). A homage, no doubt‒above all a high-carat signal.

Perhaps the best example of Miller’s insouciance. “Jay “Chef” Hicks (interpreted by Frederic Forrest), one of the “rock-and-rollers kids with one foot in their graves”, knows that he is heading for “hell”, in that mission up the river looking for a certain “Kurtz”, a translation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness into the jungle and the rivers of Vietnam. He knows that he will probably die. Yet that awareness does not impede him to enjoy the sun, a beer and... the novel by Henry Miller.

|

| Jay “Chef” Hicks (interpreted by Frederic Forrest), "heading towards hell", but still enjoying Henry Miller, Apocalypse Now (1979). |

If we look back to Henry Miller through the reading glasses of “our time”, 2022, he will appear to many as a sort of an old-fashioned oddity, a fossil of an era gone for ever‒apart from being crucified under many labels of today’s political correctness, so to speak.

Yet however many times some may attempt to bury him, he will keep resurrecting. Why?

Let us, sort of, “end” by the “beginning”:

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.”17

1„Lady Catherine observed, after dinner, that Miss Bennet seemed out of spirits…”, Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, Penguin, 2003, pp. 204-205.

2Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, Grafton Books. A division of the Collins Publishing Group, 1990. First edition Obelisk Press, Paris, 1934. P. 9.

3Orwell, George. Selected Essays, Penguin Books, 1957, “Inside the Whale”, pp. 9-50. Originally published first in 1940 in the book “Inside the Whale”.

4Orwell, pp. 40-41.

5Orwell, p. 48.

6Orwell, p.9.

7Orwell, p. 10.

8Miller, p. 57.

9Miller, p. 241.

10Orwell, p. 13.

11Miller, p. 163.

12Miller, p. 167.

13Miller, “The Colossus of Maroussi”, Penguin editions, 1982, p. 7.

14Miller, “The Colossus of Maroussi”, p. 239.

15Miller, “The Colossus of Maroussi”, p. 245.

16Confront the quote of Nietzsche’s in page 246.

17Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, Grafton Books. A division of the Collins Publishing Group, 1990. First edition Obelisk Press, Paris, 1934. P. 9.