JUAN RULFO: PEDRO PÁRAMO, THE MEXICAN

LABYRINTH.

This contribution is also available as a PDF formatted essay at

https://www.academia.edu/48723552/JUAN_RULFO_PEDRO_P%C3%81RAMO_JUAN_CARLOS_HERKEN_ENGLISH

Malaga Airport, Spain, mid-2003. I had the pleasure of going to

welcome a person who was arriving from Paris in the Andalusian city. Aware that

there could be a delay, I decided to take with me a small copy with short-stories

by the Mexican writer Juan Rulfo (1917, † 1986, full name "Juan Nepomuceno

Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno"), to ease the wait. The booklet in turn had a

somewhat romantic resonance, as it was purchased at the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore,

Paris, France, back in 1996. The current location on Rue de la Bûcherie, 5th arrondissement, is the second version. The

first one founded by Sylvia Beach in 1919, on Rue de Odéon, 6th arrondissement,

was closed during the military occupation of Paris, and never reopened.

The bookstore with a view of the

Notre-Dame Cathedral became a "refuge" quite frequented by the author

of these lines, especially between 1991-1998. Even after. Climbing the narrow

stairs and gazing at the walls crammed with books, new and used, mostly in

English, but also in other languages, was tantamount to a calendar change, a

detachment from chronological time and concerns, out there. It was on a visit,

accompanied by a beautiful and brilliant American art historian, who years

later would hold the chair at one of the most renowned universities in that

country, that I found the mini-editions of Alianza

Editorial de Madrid, and bought the volume of stories of Juan Rulfo[1].

And another by Jorge Luis Borges (* 1899- † 1986), Artificios.[2]

While waiting at the “Arrivals”

hall in Malaga I began reading “They have given us the land”, and a few minutes

later I felt the itch of “goose bumps” that began to flood me, without haste,

without opposition.

“One has sometimes believed, in the middle of this road without shores,

that there would be nothing later; that nothing could be found on the other

side, at the end of this fissured plain of cracks and dry streams. "[3]

I was no longer there, and it was hard for me

to understand why I had been there.

(First page of the "Seminar

on the short-story of three Hispanic-American authors", typed by the

author of these lines ", 1970-71. © 2021(.

I was back in South America,

between 1970-71, when I began to read the “great Mexican”, Juan Rulfo, with

whom I have the honor of sharing the saint. At the premises of an entity to be

summarized as I.L.A.R.I., located on Calle Eligio Ayala in the city of

Asunción, Paraguay, a “Seminar on the short-story of three Spanish-American

authors, Juan Rulfo, Julio Cortázar, Jorge Luis Borges” was organized,

coordinated by the great Paraguayan writer Augusto Roa Bastos (* 1917- † 2005),

who lived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, but occasionally visited Paraguay, “when

political circumstances allowed it. ... ”. I have memories of intense sessions,

very much rich and stimulating, which were written down in detail by the person

who subscribes these lines. Roa Bastos demonstrated not only a first-rate

intellectual authority, but also great generosity, and a mixture of

curiosity-respect for the youngest. One of the works that I presented was

"The treatment of time in the work of Juan Rulfo", whose draft is

still there, several decades later, hoping this author dares to resurrect it. I

insisted on underlying the concept of "metaphysical time", to which

Roa Bastos, smiling, said "... rather, psychological time."

(First page of the presentation of the “first group” on Rulfo's work, written and typed by the author of these lines, 1970-71. © 2021)

We took up the subject again on a

visit to Toulouse, France, in 1988. Roa Bastos told me of his amazement at the

ability of some students at the French university in that city, to discover new

facets in Rulfo's narratives, such as the one who, in a doctoral thesis, showed

that "... in this part you can hear the noise made by the dead ones":

"What would they discover next?", he said, astonished and happy.

In the novel Pedro Páramo (1955) by Juan Rulfo one of the secrets to "being accepted by the text" lies precisely in listening to the noise made by the living and the dead, when they walk freely through the town, Comala. Even as that noise does not sound, but it can be felt:

“I heard the sound of words from time to time, and I could tell the

difference. Because the words that I had heard until then, until I knew about

it, they did not have any sound, they did not sound. They could be felt, but without

sound, like those you hear in your dreams. "[4]

The novel came into light after

the set of stories published as El Llano

en Llamas (1953), which take place against the background of rural life in

Mexico during the "Mexican Revolution" and the "War of the

Cristeros" (1926-28). This succession of social convulsions was to affect

Rulfo's family to the utmost. After the murder of his father in 1923, and the

death of his mother in 1927, Rulfo was educated by his grandmother in

Guadalajara, Jalisco. It is the same matrix that would provide the substrate

for The Power and the Glory of Graham

Greene (see our article on this blog).

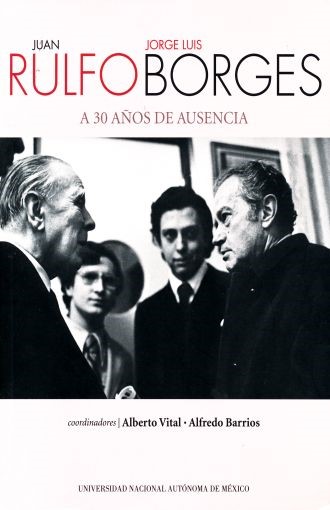

Pedro Páramo was described by Jorge Luis Borges as "one of the

best novels of the literature of Hispanic languages, and even of all

literature."[5] It

was only a few weeks ago that I became aware of the meeting of both writers, in

1976, when Borges was visiting Mexico. Both were to die in the same year, 1986.

(Jorge Luis Borges, left, and Juan Rulfo, right, 1976)

The novel begins with the

first-person narration of Juan Preciado, who promises his dying mother that he

will go to Comala, to look for his

father, Pedro Páramo. The name

already offers clues to capture the novel's underlying landscape: Pedro,

"Petrus", (stone, stones ...), "the wasteland where there are

only stones", and one could even replace "stones" by "bones”.

Thus begins the journey of Juan

Preciado, who before arriving in Comala

meets another man, a "muleteer", who tells him that he, too, is the

son of Pedro Páramo.

A woman, a friend of his mother,

will welcome him to the abandoned village, where only shadows, ghosts

circulate, crossed by empty carts, and a horse without a rider that keeps going

round and round, “aware that his employer had committed a crime".

“It’s only the horse that runs back and forth. They were inseparable.

It runs all over the place still looking for him, especially at this hour.

Perhaps the poor thing is plagued by remorse. Because even animals realize when

a wrong has been done, isn’t that so?”[6]

There is no need for us to give

more details of the plot (s) in the novel. To be noted, yes, the Leitmotive that underpin the structure

of the narrative: Adventures and misadventures of Pedro Páramo, his wives, his children, legitimate and illegitimate.

Dreams and anguish of women, at a time when aggressions arrived more frequently

than rain, the bid for money and land, the waves of the "revolution."

And a Catholic priest, Father Renterías,

confronting one of the typical crossroads of the epoch, granting indulgence to

someone who, among other things, murdered his brother and violated his niece.

“A handful of gold coins” leaves the petitioner, hoping that in this way his

deceased son would obtain God's forgiveness.

The narrative about the characters

offers us a range of tools to capture the substratum of the work: How can the

reader enter that world, deceivingly "fictitious", and rub shoulders

with men and women who seem to be swimming in the clouds. Above all: Listen to the echoes.

"Yes," Damiana Cisneros said again. This town is full of echoes.

I'm not scared anymore. I hear the howling of the dogs and let them howl. And on airy days you can see the wind dragging

tree leaves, although here, as you can see, there are no trees. There were

trees at some time, because if not, where would those leaves come from? "[7]

We do not even know if the entire

narrative is nothing more than a dreamlike construction of the narrator in the

first person, at the beginning. Commenting on the desire expressed by his

mother that he ought to make the trip, he says:

“But I had no intention to keep my promise, until I began to fill

myself with dreams, to give flight to illusions. "[8]

It should be emphasized that Pedro Páramo is written in

“Mexican-Spanish”, with singular expressions and sentence constructions, and

that it can only be apprehended within that linguistic background, which is, per se, a “Mexican vision of the world”.

The novel breathes the vapors exhaled by a society constantly shaken by revolutions

and persecutions, a Catholic Church in turn harassed by many, and venerated by

many others, which the persecution seems to make stronger. The geography of Pedro Páramo is, as his name indicates,

arid, dry land, few trees, and above all little water.

By bringing together these two writers who, each in their own way, transgressed the norms of traditional narrative, we would dare to express, repeating what we had already suggested at the beginning of the 1970s, that while Rulfo “universalizes” the “Mexican experience”, Borges “re-creates the Universal with Argentine spectacles.

Comala is the town that Rulfo uses as his own Mexican "Tower

of Babel", his "labyrinth" on the plateau, in which, without a

doubt, Ariadne’s thread is not available. At least visibly. It is the place

where the living do not know whether are still alive, and the dead do not know

whether they are still dead.

Let us rewrite it:

"Dead" and "living" keep recalling the events, in turn

changing their existential position, passing from existence on earth (Das Dasein) to existence beyond the

"wall of time" (Das-jenseits-der-Zeitmauer-Sein). Summa summarum:

The only thing that "exists" is memories. And not only in Comala. Perhaps Roa Bastos was right in

criticizing my persistence with the concept of "metaphysical time",

and insisting on that of "psychological time", even more so, today, as

we remember the Greek origin of the word "psyche", that is,

"soul".

Here follows what appears to be the

last message from Juan Preciado, but it is not. The reunion with his mother

will arrive:

“I escaped to the street looking for some air; but the heat that chased

me did not relinquish. And there was no air; only the night slowed and still,

heated by the August heatwave. There was no air. I had to suck in the very air

that came out of my mouth, stopping it with my hands before it disappeared. I

felt it coming and going, less and less; until it got so thin that it slipped

through my fingers, forever. I say forever. I have memory of seeing something

like foamy clouds swirling over my head and then washing myself off with that

foam and getting lost in its cloudiness. That was the last thing I saw."[9]

The question we asked ourselves,

weeks ago, when we began to re-read the novel Pedro Páramo: How would we react, half-a-century later?

After fifty years, the wonder is

still there, coming out of a novel with a simple and concise language, which

promises little, but offers much. And we happen to believe that, fifty years

from now on, the wonder will not have ceased.

[1] Rulfo, Juan. Relatos, Alianza Editorial, 1994.

[2] Borges, Jorge Luis. Artificios, Alianza Editorial, 1994.

[3] Rulfo, Juan. Relatos, Alianza Editorial, 1994, Nos han dado la

tierra, p. 5.

[4]

Translation from the Spanish original.

[5] Borges, Jorge Luis. Pedro Páramo, 1985, Hyspamérica, Buenos Aires, 1985.

[6] Our translation of the Spanish original.,

[7] Our translation of the Spanish

original.

[8] Our translation of the Spanish

original.

[9] Our translation of the Spanish

original.