LEV TOLSTOY: THE KREUTZER SONATA (Крейцерова соната): ON THE (IM)POSSIBILITY OF LOVE.

Whether Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Лев Николаевич Толстой, (*9 September [O.S. 28 August]1828 - †20 November[O.S. 7 November]1910), ever regretted having published The Kreutzer Sonata (Russian: Крейцерова соната), remains a question mark, whose answer may never materialise. It was a scandal right from the moment the manuscript hit the printing house, it was censored and it appeared complete, to begin with, in German in 1890. The first Russian version was printed in 1891, after the Czar of Russia, Alexander III, issued his imprimatur, nihil obstat, giving in to the pleas of clemency addressed by Countess Alexandra Andreevna Tolstoy, great-aunt of Lev Tolstoy, tutor of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna. Others argue that it was Tolstoy’s wife herself, who directly appealed to the Czar.

The initial censorship did, no doubt, enhance the interest in the opus. It enjoyed quick success, and it remains a canon of European literature, right to our epoch. There are at least 15 film-versions, first two in Russia, 1911 and 1914, the latest 2008 in the United Kingdom (directed by Bernard Rose) and in Spain, 2013. Not to mention the numerous adaptations for the theatre.

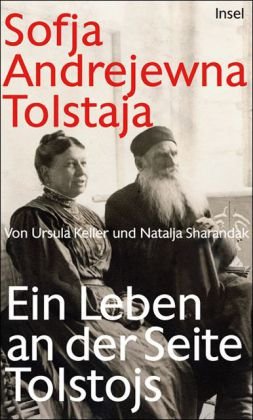

But it also generated yet another source of conflicts with his wife, perhaps even an insurmountable estrangement, Sofja Andrejewna Tolstaja, Соoфья Андреeевна Толстая (*3. September, O.S. 22. August 1844, †4. November 1919 in Jasnaja Poljana), who bore Tolstoy 13 children and with whom she remained married for 50 years. Sofja Andrejewna, born “Behrs”(German ascendancy) felt the need to reply in her own words, thus writing “Whose Fault? The narration of a woman”. Written in the years 1892-1893, it was only published hundred years afterwards, in 20081.

A first summary (but not the only one, and above all not the last one): The first-person narrator (who remains unnamed and almost invisible) describes a train trip, in which a man (“prematurely aged”) is going to join a discussion between the passengers of a compartment about the perennial issues of love, sex, marriage, social constraints and the uncontrollable instincts of both men and women. We invite the reader to get acquainted with the never exhausted disquisitions on the man-woman problematic in the text of the novel in itself. Here we are more interested in presenting the literary structure, and to unveil two or three clues which may help us to understand what indeed did Tolstoy attempt to achieve with such an aggressively polemic, naked and remorseless dissection of the traps and delusions threatening the search for love, both outside and inside marriage.

The first version of the novel was written on the occasion of the “silver-anniversary” of the marriage between Lev and Sofja. We could not possibly accept the suggestion that it was a “present”. It was named after Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, Sonata No. 9 in A Major for piano and violin, Op. 47 ("Sonata per il Pianoforte ed uno violino obligato in uno stile molto concertante come d’un concerto"), dedicated to the French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer (in fact the second dedicacé, the first one having fall out with Beethoven, hence the defenestration).

Shortly afterwards, Tolstoy wrote a kind of a “postface” to the novel, to answer the many queries of readers, who were as much puzzled and no less intrigued as to what on earth was the message intended by the Russian writer in that “short-novel” (Novelle in German).

The main male character is thus a Russian who tried to escape from his riotous juvenile debauches into marriage and children, only, after a few tranquil years, to drown deeper into the mud of unresolved physical attractions, repulsions‒and suspicions. It seems that love is always threatened by filth and treason, and that marriage hardly provides a sanctuary. An echo arrives from far away: “So foul a sky clears not without a storm”, Shakespeare, King John, Act 4, Scene 22.

Two quotes from the Bible (Matthew) open the novel, hinting already that we are going to need a tremendous amount of holy-water to get to the end.

It is not surprising that in the preface to the bilingual (French-Russian) edition, which we first used to get some acquaintance with this novel, Nina Kehayan begins by asking:

“D’ou

vient le malaise dans lequel La Sonate à Kreutzer laisse le

lecteur?“3

What is the origin of the malaise which suffocates the reader?

She adds, some lines afterwards, “...one is tempted to scream

“this is too much” while closing the book, as such

is the bleakness impregnating every page…”

Many of Tolstoy’s friends were at least puzzled, if not annoyed and angry. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Антон Павлович Чехов) (*1860-†1904), a trained surgeon, who guarded a keen empathy but also a healthy distant towards some of the awkward positionings of “Big Brother” Tolstoy, was adamantly critical of the way Tolstoy tackled the relationship between male and female, and disregarded every scientific proposition which Tolstoy may have attempted to bring onto his side of visioning love and sex.

Yet a warning (others are still to come) should be given ad initium with regard to the Russian original and the translations, as specified by one translator into English of this novel and other stories:

“On comparing with the original Russian some English translations of Count Tolstoy’s works, published both in this country and in England, I concluded that they were far from being accurate. The majority of them were retranslations from the French, and I found that the respective transitions through which they had passed tended to obliterate many of the beauties of the Russian language and of the peculiar characteristics of Russian life. A satisfactory translation can be made only by one who understands the language and spirit of the Russian people. As Tolstoy’s writings contain so many idioms it is not an easy task to render them into intelligible English, and the one who successfully accomplishes this must be a native of Russia, commanding the English and Russian languages with equal fluency.”4

We have no intention of claiming to have achieved such a status, albeit we will do our best, using our knowledge of the languages concerned, to at least place some warning-signs across the Tolstoyian language minefield.

Let us, before embarking into an interpretation of the “message(s)”, or rather apocalypses, underpinning The Kreutzer Sonata, just provide a summary of what in fact happens in this short-novel. It is still worth reading today, albeit better be it done privately, as the current eruptions of “political correctness” may as well send the reader of such opus into prison.

It must be read also to appreciate, once again, the splendid skills of Tolstoy as a writer and a story-teller. We have to wait 27 pages to encounter the first mention of a concrete family-name, which identifies the key male character, Pozdnyshev, who describes himself as having been a land-owner, completed university studies and a “maréchal de la noblesse” (… и был предводителем...)5 In summa, an educated member of the “upper class”. He is going to unravel throughout the train-voyage his drama and the tragedy which will accompany all his life (if such a privilege, life, were still to be available to him.

Tolstoy gives, right at the beginning, specific physical and mental traits to the travelers, enabling him to avoid the usage of family-names, and even first-names by simply referring to “an ugly and aged woman, with a tormented face, who smoked and wore a bonnet and a masculine overcoat”, her acquaintance, “an early-forties man, talkative, carrying new and elegant suitcases”, and “a man, not really tall, whose movements were untoward...”6 It is only when we get to the key tragic scene in the novel, that Tolstoy starts naming some of the other personages in the novel:“Our valet de chambre Egor…”, “Vasia, the sister of my wife…”, “Ivan Fedorovich, the surgeon…”, “Lise, one of my children...”

His wife seeks refuge in the piano, and the family hires a violinist, Troukhatchevsky, to aid the woman in improving her musical skills. The two seem to insist on playing Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata. At first everything would unfold peacefully. One day, however, Pozdnyshev would arrive suddenly back to his home in Moscow, and will find the two, his wife the pianist, and the violinist, seated together. He infers only one thing (“treason!”) and a dagger will come to life, in order to end a life, that of his wife.

In one of the many attempts by Pozdnyshev to cogitate some explanations for the inexplicability of his actions, or simply to camouflage his Krankheit, he asserts that men only think of, and exists for, “Wein, Weiber und Gesang” (written in German in the original Russian text)7, “Wine, females and chant”, hence hinting that the wrong combination of those three delicatessen, or the excessive consumption of any of them lead to debauch, illness, madness and … tragedy. We do not know whether Tolstoy knew that that German motto is usually attributed to Martin Luther (although some disagree), who would have written “Wer nicht liebt Wein, Weib und Gesang, der bleibt ein Narr sein Leben Lang” (He who does not love wine, woman and chant, will remain a fool all his life”). The motto, albeit expanded, even figures in the second strophe of the German national anthem (nowadays never sang):

“Deutsche Frauen, deutsche Treu,

Deutscher Wein und deutscher Sang

Sollen in der Welt behalten

Ihren alten schönen Klang…“

And Johannes Strauss composed a waltz (1869) with the same title: “Wein, Weib und Gesang”.

But there is a crucial difference. The quote in German in the Russian original, as well as in its translations into English and French mentions “Weiber”, not “Weib”. “Weiber” is the plural of “Weib”, hence, “females” not “a female”. In the footnote accompanying the Russian text, the plural form is also used: “женциниы». Tolstoy, or its editors, also translated “Gesang” as песня, although the latter in German is “Lied”.

Did Tolstoy deliberately alter the original version, to reinforce the message (through Pozdnyshev) that a man is encouraged to be libertine? The motto supported by Luther and other Lutheran writers, as well as by Johann Strauss, which eulogises the joys of love, singing and wine, as pertaining to the nature of men and women, is hence biased towards a much more raucous, libertine view of the world.

And then we confront the eruption of a pathological interpretation (or misinterpretation) of music, again through Pozdnyshev:

“They played the “Kreutzer Sonata '' by Beethoven. Do you know the first presto? Do you know it?, he screamed. Ah! What a dreadful thing, that sonata. Above all that movement. And music altogether is a dreadful thing. What indeed is this thing? I don’t understand it. What is music? What does it do? And why does it affect the way it does? It is said that music aims to elevate the soul… what a stupidity, what a lie (untrue)!.”8

“It inflames the wrong, unnecessary feelings at the wrong moment…” might be the summary we can inflict upon the Philippica against music – or at least against music like the Kreutzer Sonata.

“Let us take as an example that Sonata Kreutzer, the first presto. Could one really play such a presto in a saloon amidst ladies en décolleté?“9

Of course one could. Pozdnyshev simply cannot understand that the eruption of innermost feelings provoked by a masterpiece of art does not necessarily have to be satiated, and assuaged, by sensual embraces. And it all depends on the interpretation. As Beethoven himself seemed to have defined it, “it is a man trying to reach his lover, he is stuck in bad weather and his lover may not wait for too long, hence, a certain “agitation”. It is, no doubt, a female-male dialogue. Herewith two examples for comparison. First the rather suave, tranquil, almost-bucolic interpretation by Anne Sophie Mutter (violin) and Lambert Orkis (piano)10. They required 15:65 for the first-movement. Now listen to the fiery, “Russian” interpretation by two giants of the 20th century11, Leonid Kogan (violin) and Emil Gilels (piano), Leningrad, 1964. They required only circa 11 minutes for the first-movement.

Anne Sophie Mutter (violin) and Lambert Orkis (piano)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A usual interpretation of The Kreutzer Sonata is that of a thunder against seeking excessive delights in the fleshy entanglements between men and women, perhaps even an advocate of chastity (at a given moment…), as a way of keeping a healthy life, or at least a not too conflict-loaded life. But did Tolstoy really have to “extreme” the issue by constructing a male character who is simply krank, a low-class hedonist, driven by satanic impulses, un homme malade?

The possible onslaught against Tolstoy of having “overdone” it was on the table, ad initium. Hence the initial censorship. Yet there is also humour in the novel, mostly a sarcastic one.

Why does Tolstoy refuse to identify the first-person narrator and all the discussants in the voyage en train, except for Pozdnyshev, but only after twenty-seven pages? It is the description of a confession in a dark theatre, populated by invisible, faceless people. Perhaps a paraphrase, Pozdnyshev in fact is confessing to God‒and the world, to an anonymous public.

Pozdnyshev also receives a specific physical trait, an awkward one:

“from time to time he issued strange sounds, resembling an expectoration or a broken laugh.”12

Thereby Tolstoy indicates that, in his most innermost that man is completely broken.

At the end of the narration, Pozdnyshev does not cease to cry, and only says: “Well, forgive me…” (Ну, простите…). He then lies in his banquette and covers his face. The first-person narrator relates that he needs to leave the train at the next station, but before he touches Pozdnyshev, who was not sleeping, and says to him: “Goodbye…” (прошайте), extending his hand. Pozdnyshev also extends his hand, “ony just smiling, yet in such a pitiful war, that I wanted to cry”, says the first-person narrator. And then Pozdnyshev again, “Yes, forgive me.” As the French translator adds in a footnote at that page, простите and прошайте are homonyms, implying that the destroyed and repented former husband “had been forgiven”, after his tearful confession, echoing en avant what Tolstoy is going to argue at the end of his “postface”: Христианское учение идеалв есть то едниое учение, которое может руководить челоьечеством 13, «The Christian doctrine of the Ideal is the only doctrine capable of conducting mankind.”

What does Tolstoy argue in the famous “postface”? He goes against what he called “perceived and accepted” customs in the Russian society at the time (bot not only there) regarding sexuality and marriage, rejecting the postulate that sexuality must be enacted always, as it is supposed to be healthy. He also rejects the low-voiced acceptance of infidelity” as a normal phenomenon, even within marriage, a supposed in-born impulse in men and women. Thirdly, he spurns the assertion that the task of “procreation” could diminish the joy of carnal embraces. And, to the astonishment of almost everyone, he criticises the efforts of poetry and literature in general to present the “search for sensual love” as the most sublime, soul-enhancing task. Humanity has other tasks, much more relevant and God-conforming. He may have a point there...

Is this a call for “chastity” as the healthiest way of life?

Tolstoy did undergo profound changes during the 1870s, remaining a Christian, albeit an anarchic and pacifist, an adherent of “non-violence” (which was to influence Mahatma Gandhi) but becoming also an advocate of vegetarianism. He acknowledged that the figure of Pozdnyshev was an “extreme case”, that deliberately sharpened the traits of an ill, obsessive jealous man who never attained a certain inner-equilibrium, mainly because he lacked a sense of appreciation of art. Hence his apprehension vis-à-vis music, suggesting even that, as indicated by Confucius, that “the state” should control music in order to avoid stirring diabolical passions, unrestrained desires among the populace.

Tolstoy then as a “Provocateur”? To some extent yes, in order to warn of the dangers accompanying excessive “hedonism”. In that sense, at least, a suitable reminder for our age.

The reader may notice that this contribution to the blog comes after the one on Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer. It is not a coincidence.

Berlin, VII MMXXIII

1German edition, Munich, 2008, Manesse Verlag.

2It is also the epigraph of the novel Nostromo, by Joseph Conrad.

3Tolstoï, Léon. La sonate à Kreutzer Крейцерова соната, Folio Bilingue, Edition Gallimard 1994, Nina Kehayan, revised the French translation in conformity with the final text of the Russian edition of the Complete Works of Tolstoy, Moscow, 1936, Volume 27. She also wrote the preface and the accompanying notes. P. 7. Translations from French and Russian into English are the responsibility of the author of the blog, unless otherwise indicated.

4 Translator´s preface in the The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories,.. The version therewith presented of The Kreutzer Sonata has been abridged at many levels, including the disappearance of full paragraphs and phrases, to begin with, the two first phrases “at the beginning”.

6 Pages 28-29.

7 Pages 136.

8 Pages 222-223.

9 Pages 226-227.

10 Beethoven.Violin.Sonata.No.9.Op.47.kreutzer.[Anne-Sophie Mutter.-.Lambert.Orkis]

11 Beethoven - Violin sonata n°9 "Kreutzer" – Leonid Kogan / Emil Gilels, Leningrag, 29.03.1964

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aC7qA9NRBNo I. Adagio sostenuto - Presto 0:00 II. Andante con variazioni 11:15 III. Presto 26:18

13 Pages 330-334.

_beethoven-violin-sonata-no-9-op-47-kreutzer-anne-sophie-mutter-lambert-orkis.jpg)