GIUSEPPE TOMASI DI LAMPEDUSA,

IL GATTOPARDO: HOW TO CHANGE EVERYTHING, SO THAT

EVERYTHING (ALMOST) REMAINS AS IT WAS.

A

painful confession, to begin with: I have seen the Luchino Visconti

(*1906-†1976) film

version (1963)

on many occasions), first time end of the 1960s, but I confronted the

novel (1958, (Il Gattopardo, The Leopard) as such only last

year, as chance allowed a translation into German to fall on my

hands. The original Italian version was bought shortly afterwards

A

possible explanation for this décalage may have

been the desire to read it in Italian, as I suspected that only the

Italian text would suffice to let the images and sounds reverberate

again, in the primaeval matrix, to confront, once more, that most

precious of questions: Can a magisterial film subsume all the

essence of such a novel? Provisional answer: A substantial part of

it, yes, but some layers remain hidden in the texture of the novel. A

not to be underestimated caveat: The film stops at the end of

“Parte VI”, thus not incorporating “Parte VII” and “Parte

VIII”, which take the action well beyond the 1860s, into the early

20th century. A tiny proportion of “Parte V” is

incorporated as a dialogue of the Padre Pirrone with peasants

in “Parte II”.

Both

decisions are very clever, underlying the necessarily different ways

of “handling” a novel and its “film version”. By limiting the

action to the interval between 1860 and 1862, the “essence” of

the novel is maintained, yet at the same time, the “saga” is kept

compact and tense, as there are no “post-faces” stretching the

narration over half-a-century which may dilute the core of the

handling and the descriptions. A fuller integration of “Parte V”,

which takes us with Padre Pirrone into his place of birth, would have

been an unnecessary deviation from the “main stream”, the

narration of the key events which underpinned the backbone of the

text.

Thus

this blog’s entry is an invitation, in particular to those who have

seen the film, to read the novel, if possible in Italian. It would

help to enjoy the cinematographic version

even more, and to understand why there are

descriptions and subdued allusions that cannot be transported onto

the cinema-screen.

Visconti’s

film (1963) is not only his capolavoro, it is one of the

capolavori in the whole history of Italian cinema, and one

of the greatest films ever made. Such accolades remain almost

uncontested, as Visconti, as well as his camera and photography

director, Giuseppe Rotunno (*1923-†2021)

somehow managed to count on the technical advise of Rembrandt,

Velázquez, Dürer, Caravaggio, Goya, Manet, Renoir et cetera…

Try taking out almost any frame of the film, “frame” it as such,

and hang it on the walls of any beaux arts museum: Nothing

extraneous has been incorporated. The whole panorama is even

enhanced.

A German edition

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Yet

you cannot achieve such a pinnacle in cinema, unless the original

source bathes itself in very high-carat. Indeed, the novel Il

Gattopardo is one of the most fascinating,

emblematic European novels of the 20th

century. And perhaps also the most relevant in generating

ex post, its own political theory regarding “continuity

and change” in society: il gattopardismo.

Giuseppe

Tomasi di Lampedusa (Palermo, 23 dicembre 1896 – Roma, 23

luglio 1957), “11º principe di Lampedusa, 12º duca di Palma,

barone di Montechiaro, barone della Torretta, Grande di Spagna di

prima Classe (titoli acquisiti il 25 giugno 1934 alla morte del

padre)”,

could not see his beloved novel printed, having been refused by two

major Italian publishing houses. It came out after his death,

reaching a very large audience immediately, and it has been

translated into almost every language. He was in no doubt as to the

value of his opus, as transpired in his last letters before his

death. Anyone reading the first pages in Italian would realise, at once, that we have in our hands a work of art into which the

author had invested his soul, his blood, his remembrances, his dreams

and his nightmares, to construct a fantastic, penetrating fresco of

an epoch and of a family (his own, roughly speaking…), poetizing

the landscape of Sicily to the point that we can smell the odours of

the olives and the vineyards. We touch the salted drops of water of

the Mediterranean, transported by the wind onto the arid hills and

mountains of that land which had belonged to the Phoenicians, the

Greeks and the Arabs. The Sicilians being the mixture of all that‒and much more. Let us just visit the “garden for the blind”,

around the palazzo of il

Principe de Salina:

“Era

un giardino per ciechi: la vista costantemente era offesa ma

l’odorato poteva trarre da esso un piacere forte ben che non

delicato. Le rose Paul Neyron le cui piantine aveva egli stesso

acquistato a Parigi erano degenerate: eccitate prima e rinfrollite

dopo dai succhi vigorosi e indolenti della terra siciliana, arse da

lugli apocalittici, si erano mutate in una sorta di cavoli color

carne, osceni, ma che distillavano un denso aroma quasi turpe che

nessun allevatore francese avrebbe osato sperare. Il Principe se ne

pose una sotto il naso e gli sembro di odorare la coscia di una

ballerina dell’Opera (Parigi),

“It

was a garden for the blind: The eyes were constantly offended but the

nose could draw from it a strong pleasure, albeit not a delicate one.

The Paul Neyron roses, whose cuttings he had himself bought in

Paris, had degenerated: Excited first and weakened later by the

vigorous and indolent juices of the Sicilian earth, burned by the

apocalyptic July, they had turned into a sort of flesh-coloured

cabbage, obscene, but distilling a dense, almost indecent aroma that

no French cultivator would have dared hope for. The Prince put one

under his nose: He seemed to smell the thigh of a dancer from the

Opera (Paris).”

None

of the above was transposed onto the screen-it would have been almost

impossible, had someone attempted it.

“Maggio

1860. “Nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. Amen”. La recita

quotidiana del Rosario era finita.” Beginning of the novel and the

film.

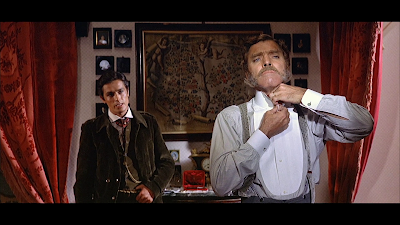

“The daily recital of the Rosary was finished.” from left to

right: Padre Pirrone (Romollo Valli), Don Fabrizio

Corbera, Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster), Concetta Corbera,

eldest daughter of il Principe (Lucilla Morlacchi), Princess

Maria Stella of Salina, Don Fabrizio's wife (Rina

Morelli). Il Palazzo Salina is in reality the “Villa

Boscogrande” in Palermo.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This

is not only a “historical novel”, it is a love-song to Sicily,

with all its tremendous contradictions. Not to be forgotten: This is

also a “Catholic novel”...

Most

of the action takes place at the time of the Italian Risorgimento, centered on the commotion and upheavals caused by the landing of

Giuseppe Garibaldi and his “proletarian” (but not only) army,

known as The Thousand, I Mille di Garibaldi, on the

Sicilian coast, May 1860. Soon they will overthrow the Kingdom of

the Two Sicilies, run by the Bourbons, and integrate the island

to a new, unified Italian Kingdom under Victor Emmanuel (Vittorio

Emanuele II, *1820-†1878,

as from 1861 “King of Italy”, “Padre della Patria”)

The

mirror which reflects and reverberates all those changes is the

Salina family, headed by il Principe Fabrizio, a tall, robust

patriarch who imposes a strict Roman Catholic conduct and ritual upon

its family, and devotes himself, together with Padre Pirrone,

to science and astronomical observations, Don Calogero Sedàra

which seemed to find some positive echo in Paris. He is actually of

half German descent, half Sicilian.

“Ma

nel sangue di lui fermentavano altre essenze germaniche ben più

incomode per quell’aristocratico siciliano nell’anno 1860, di

quanto potessero essere attraenti la pelle bianchissima ed di capelli

biondi nell’ambiente di olivastri ed di corvini: un temperamento

autoritario, una certa rigidità morale, una propensione alle idee

astratte che nell’habitat molliccio della società palermitana si

erano mutati in prepotenza capricciosa, perpetui scrupoli morali e

disprezzo per i suoi parenti e amici che gli sembrava andassero alla

deriva nel lento fiume pragmatistico siciliano.”

"But

other Germanic essences fermented in his blood, much more

uncomfortable for that Sicilian aristocrat in the year 1860, however

attractive the very white skin and blond hair may appear in the

environment of olive trees and ravens: An authoritarian temperament,

a certain moral rigidity, a propensity for abstract ideas that in the

sloppy habitat of Palermo’s society had turned into capricious

arrogance, perpetual moral scruples and contempt for his relatives

and friends who seemed to him to swim adrift in the slow Sicilian

river of pragmatism.”

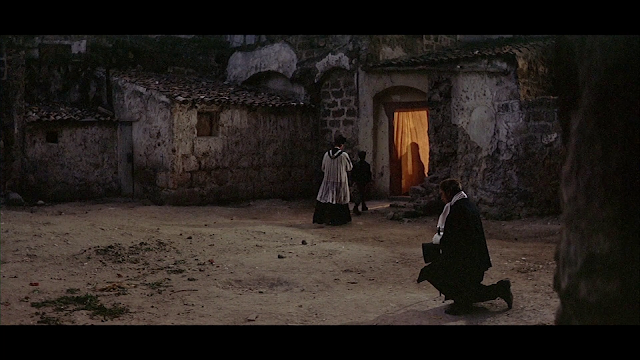

No,

this is not “a Caravaggio”, albeit it seems, but a portrait of il

Principe de Salina and Padre Pirrone, travelling to

Palermo. “Che bel paese sarebbe questo, Eccellenza, se…”,

“”What a nice country would be this, if…”, says Pirrone to il

Principe, who interrupts him, “Se non vi fossero tanti

Gesuiti!”, “If there weren't too many Jesuits!”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

His

“alter ego” is composed of camouflaged sensuality and eroticism,

which allows him to enjoy half-clandestine liaisons, be either in

Paris or in the suburbs of Palermo.

“I

ruderi libertini!”, “what a wrack of libertines!”, Tancredi

(Alain Delon), to his uncle after a concealed naughty libertine night

in Palermo.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Instead

of taking refuge by the “British”, as his brother does on

learning of the advance of Garibaldi and his soldiers, il Principe

de Salina soon adopts a much more pragmatic, conciliatory

attitude:

“Molte

cose sarebbero avvenute, ma tutto sarebbe stato una commedia, una

rumorosa, romantica commedia con qualche macchia di sangue sulla

veste buffonesca. Questo era il paese degli accomodamenti, non c’era

la furia francese; anche un Francia d'altronde, se si eccettua il

Giugno del Quarantotto, quando mai era successo qualcosa di serio?”

“A

lot of things would happen, but it would all be a comedy, a noisy,

romantic comedy with a few bloodstains on the buffoonish robe. This

was the land of “arrangements”, there was no French fury; even in

France, on the other hand, with the exception of June 1848, when had

anything serious ever happened?”

“Se

non ci siamo anche noi, quelli ti combinano la reppublica. Se

vogliamo que tutto rimanga comme è, bisogna che tutto cambi. Mi sono

spiagato?“

Tancredi giving a formidable political lesson to his uncle, il

Principe de Salina. “….Unless we take the lead again, those

guys are going to concoct a republic upon us. If we want everything

to remain as it was, everything needs to be changed. Have I made

myself clear?”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

That

reflects also his way of handling employees and tenants, which

combined distance, but also affection‒and

tolerance. Be either by “ignoring” the cases of lemons which had

been stolen by one of his devoted administrators, or “forgetting”

to ask for the annual delivery of tributes in species from his

tenants, specially when he visits Donnafugata, that

refuge which allows him to escape from gossips and the skirmishes in

Palermo, going there “to rusticate themselves”.

Padre

Pirrone attempting to digest, without too much stomach-pain, the

intimate confessions of il Principe de Salina, who has just

been remonstrated because of his naughty escapade to Palermo. “Seven

children I’ve had with her! (his wife) Seven! And do

you know what, Padre? I have never even seen her navel…”

Dialogue added by the screenwriters.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Entry

of the family of il Principe de Salina into the Cathedral

(Chiesa Madre) in Donnafugata, to assist at the

traditional Te Deum offered to the family on its arrival at

the town. Don Francisco "Ciccio" Tumeo (Serge

Reggiani), organist and an old friend of il Principe,

plays the melody of Violeta’s begging for love, Amami, Alfredo,

in La Traviata of Giuseppe Verdi (*1813-†1901).

The melody is also contained in the overture of the opera.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No,

this is not “a Rembrandt”. This is a scene in the cathedral, at

the beginning of the Te Deum. On a wall outside one can read

the inscription: VIVA GARIBALDO. It should have been “Garibaldi”,

though in the novel it is written “Viva Garibbaldi”. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To

be noticed: The facial expression of Don Calogero Sedàra, mayor

of Donnafugata (Paolo

Stoppa), (left),

who gazes at the Salina family, convinced that the moment has come,

to seal an “alliance” between the slowly crumbling aristocracy

and the ambitious new “bourgeoisie”, that is, an “alliance”

between “prestige” and “money”. To be accomplished, as God

disposes, only through “marriage”. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A

combination of Rembrand, Velázquez, and Dürer. The Salina family

at its privileged position in the Cathedral, still bearing tonnes of

dust accumulated during the journey.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The

long expedition (“Il viaggio era durato tre giorni ed era stato

orrendo”)

in carriages of the family to Donafugatta, through the arid

landscapes, where at times trees were unknown creatures, was perhaps

one way of torturing themselves, or in the case of il Principe,

that of paying for his sins. “Mademoiselle Dombreuil, “la

governante francesa”, who had spent some years in Algeria could

not contain herself: “Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, c’est pire qu’en

Afrique!”.

There he would be received officially, with all the pomp the town

could afford, by Don Calogero Sedàra, major

of Donafugatta, a

„self-made man“ rapidly accumulating wealth, fierce advocate of

the “revolutionaries”, jet admirer of the Salinas, of awkward and

inelegant manners, yet shrew and pragmatic. Her daughter Angelica

will soon captivate Tancredi, the nephew of il Principe de

Salina.

Angelica

(Claudia Cardinale), only daughter of Don Calogero Sedàra, mayor

of Donnafugatta, makes her entry into the

sumptuous rooms of the Salina’s palazzo in Donnafugata.

A hint of Pierre-Auguste Renoir but also

Édouard Manet.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“...ed

entrò Angelica. La prima impressione fu di abbagliata sorpresa. I

Salina rimasero col fiato in gola. Tancredi senti addirittura come

gli pulsassero le vene delle tempie. Sotto l’impeto della sua

bellezza gli uomini rimasero incapaci di notare. (…) Sotto la massa

dei capelli color di notte avvolti in soavi ondulazioni, gli occhi

verdi albeggiavano, immoti come quelli delle statue e, com’essi, un

po’ crudeli. (…) recava nella persona la pacatezza,

l'invincibilità della donna di sicura bellezza.”

“…

And Angelica entered. The first impression was one of dazzled

surprise. The Salinas stood there with breath taken away. Tancredi

even felt how the veins in his temples were throbbing. Under the

impetus of his beauty, men were unable to notice. (...) Under the

mass of night-coloured hair wrapped in gentle undulations, her green

eyes gleamed motionless, like those of the statues and, like them, a

little cruel. (…) She walked slowly (…) letting emanate from of

her the calmness, the invincibility of a woman sure

of her beauty. "

Reaction

of il Principe de Salina…

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reactions

of Tancredi and of Concetta, one of the daughters of il

Principe de Salina, who is supposed to be on her way to become,

before long, Tancredi’s bride.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The

key dialogue between il Principe and Don Ciccio, while

hunting early in the morning:

„La

verità, Eccellenza, è don Calogero è molto ricco e molto influente

anche; che è avaro (cuando la figlia era in collegio lui e la moglie

mangiavano in due un uovo fritto) ma che quando occorre sa

spendere.(…) ma un mese fa ha prestato cinquanta onze a Pasquale

Tripi che lo aveva aiutato nel periodo dello sbarco; e senza

interessi, il che è il pio grande miracolo che si sia visto da

quanto Santa Rosalia fece cessare la peste a Palermo. Intelligente

come un diavolo.“

“The

truth, Excellency, is that Don Calogero is very rich and very

influential too; we know that he is a miser (when his daughter was at

school he and his wife used to share a fried egg) but when something

happens he knows how to spend (…) a month ago he loaned fifty

“ounces” to Pasquale Tripi, who had helped him at the time of the

disembarkation; and without interests, which is the biggest miracle

to have been seen around here since Santa Rosalia extinguished

the pest in Palermo. As intelligent as the devil…”

Don

Ciccio, who voted “no” in the plebiscite (albeit no “no

vote” was registered in Donafugatta would consider the “marriage”

between Tancredi and Angelica as “treason, the end of the

Falconeris (family of Tancredi) and even of the Salinas…“

The

battle on the streets of Palermo. Please confront “The execution of

Maximiliam” (1868/69) by Édouard Manet. And also “Los

fusilamientos del 3 de mayo de 1808”, “Execution of the Citizens

of Madrid”, completed by Francisco de Goya in 1814.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Battle

on the streets of Palermo. Please confront “Los desastres de la

guerra” (The Disasters of War), a series of 82 prints created

between 1810 and 1820 by Francisco de Goya.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The

future husband of Angelica would return with a comrade, wearing the

new uniform of the regular forces of the new Kingdom of Italy, making

haste to distance themselves from the “proletarian

revolutionaries”:

„Ma

insomma, voialtri garibaldini non portate più la camicia rossa?“.

I due si voltarono come se li avesse morsi una vipera. „Ma che

garibaldini e garibaldini, zione! Lo siamo stati, ora basta“ (…)

Con quelli lì non si poteva restare (…) Mamma mia che gentaglia!

Uomini da colpi di mano, buoni a sparacchiare, e basta!“

„But,

after all, you the garibaldini no longer wear the red shirt?”

The two turned around as if a snake had bitten them. “But, uncle,

forget the garibaldini and garibaldini! We had been,

and now it is all over. We could not have possibly remained there

with those guys! Mamma mia, what a mob! Good for ambushes and

looting, and that’s all!”

Sharply

attacked by the Italian Communist Party (to which Visconti felt very

close) when it was first screened, the film was accused of being

“politically conservative”, expressing a “reactionary ideology”

by more or less by the whole spectrum of the Italian left.

Visconti even concocted a different version, adding much more

references to the “class struggle” and the “peasant resistance”

(which were eliminated of the version presented at the Venice

Festival), but even that concession did not seem to placate the

vociferous critics, the insistence being upon “il

anti-storicismo” of the film. That the vision-of-the-world

transpiring out of the novel, and out of its cinematographic

translation, was one of rejecting the possibility of “progress”,

or “real changes” taking place in society. Or at least in Sicily.

Should

that really be the final conclusion to be extracted? Does the

statement “...If we want everything to remain as it was,

everything needs to be changed…” really implies that

“revolutions” are much more “superficial” than what they

appear at first? No one could possibly imagine that Giuseppe Tomasi

di Lampedusa attempted to deny the possibility of change, the

inevitability of at least some “progress” taking place, albeit

perhaps at much slower rhythm.

I

happen to believe that the gattopardismo should not be

interpreted as a cynical approach to history, insisting on the

futility of “vociferous and radical speeches”, and even of

thunderous street battles and brief, or even long, “civil wars”.

It is rather the conviction that there is a constant need to find a

new “equilibrium”, let us call the “Lampedusian

equilibrium”, that there is an innate trend in society to

“re-arrange” the bits and pieces, to find a new way of

“coexistence”. In the concrete case of this Sicilian novel, it

means probably that:

“...the

upper classes agree to behave a “little less conservative”, and

the “revolutionaries” agree to behave much more “less

revolutionary”...

“...e

il giorno del matrimonio consegnerò allo sposo venti sacchetti di

tela con mille “onze” ognuno…”

Don Calogero enhancing the pre-nuptial deal between Tancredi

and Angelica, by “...on the day of the wedding I shall give to the

bridegroom twenty linen sacks, each of them containing 1,000 ounces

of gold…” Padre Pirrone “monitors” the whole

transaction, while “reading” unobtrusively in a corner.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Angelica

yearning for the long-awaited, just-about repressed first intimate

communion with her fiancé, while playing and exploring the labyrinth

of forgotten and uninhabited rooms and corridors in the Salina’s

palazzo in Donnafugata, which

constitutes in fact “il nucleo segreto centro

d’irradazione delle irrequietudine carnali del palazzo...”,

the secret core, the centre of

the radiations of the carnal anxieties of the palazzo…”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And those days, playing like

excited children and caressing the frontier of sensuality, but not

trespassing it, were to constitute the best moment of their lives:

“Quelli

furono I giorni migliori della vita di Tancredi e quella di Angelica

(…) Quando furono divenuti vecchi e inutilmente saggi I loro

pensieri ritornavano a quei giorni con rimpianto insistente: erano I

giorni del desiderio sempre presente, perché sempre vinto, dei

letti, multi, che si erano offerti e che erano stati respinti, dello

stimolo sensuale che appunto perché inibito si era, un attimo,

sublimato in rinunzia, cioè, in vero amore.”

"Those

were the best days of Tancredi's life and that of Angelica (...) When

they became old and uselessly wise, their

thoughts returned to those days with insistent regret: they were the

days of ever-present desire, because always conquered; of beds, many

of them, which

had offered themselves, and which

had been rejected; of the sensual stimulus which, precisely because

it was inhibited, was, for a moment, sublimated into renunciation,

that is, into true love. "

21

pages, between pp. 211-232, in the novel are used to describe the

„ball“ in the palazzo Ponteleone

(in the film the location is the palazzo

Valguarnera-Gangi, in Palermo). That represents

about 10 percent of the pages of the novel which were

“screen-written” in the film. Yet the screen version of that

sequence occupies almost one third of the length of the film.

“The

impossible love”, il Principe de Salina dancing a waltz with

Angelica (at her request…), letting eyes and words communicate that

well-hidden, unspoken desire. Tancredi watches that dancing

exhibition, just about containing jealousy and fear.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Is

that a disproportionate “zoom-in” of such a tiny proportion of

the text? Not quite, although there is no doubt that Visconti and his

teams decided to widen that evening at the palazzo Ponteleone,

fist of all, in order to apply a sumptuous choreography, and let

glittering attires, whose colours had been meticulously premeditated,

glide before our eyes, as an incessant flow of images, as if the best

tableaux of the best museums have been joint together, and let to

float around, distilling gold and silver:

“the

ball in the palazzo, which runs as a favourite in the competition to

designate the most beautiful film-sequence of all time…”

Visconti

also extends the “ball scene” to let it operate as a magnetic

field, a reverberating human landscape of all the Leitmotiven,

the themes of the whole novel. It is the “presentation in society

(high)” of Angelica, and even of her father, whose clothes have

been selected by his future son-in-law. It is the reunion of il

Principe de Salina with his relatives, and even with his former

lovers. The new military officers turn in, who in the next early

morning are going to execute the “rebel soldiers”, those who did

not want to let the “revolution” fade away. The new Lampedusian

“equilibrium” is consecrated and rejoiced.

The

young ladies kicking around, sitting, or even jumping like pigeons

caught in a whirlwind of desires and excitements, letting their fans

act as wings, the colours of their dresses representing a harmony a

white, orange and gold, almost a reflection of the walls in which

they celebrate the evening.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It

is the mingling and contrast between “youth” and “old-age”,

the awareness of the brief splendour of gallantry and vanity, and the

inevitability of death.

A

perfect composition of colours: white, then dark-blue, crowned by the

red roses.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“...la

carrozza se fermò; si sentiva un gracile scampanellio e da una

svolto comparve un prete recante un calice col Santissimo; dietro un

chierichetti gli reggeva sul capo un un ombrello bianco ricamato in

oro; davanti un altro teneva nella sinistra un grosso cero acceso, e

con la destra agitava, divertendosi molto, un campanellino di

argento. Segno che una di quelle case sbarrate racchiudeva un’agonia,

era il Santo Viatico. Don Fabrizzio scese, s’inginocchio sul

marciapiede, le signore fecero il segno della croce, lo scampanellate

dileguò nei vicoli che precipitavano verso S. Giacomo, la calèche

con i suoi occupanti gravati di un ammonimento salutare s’incamminò

di nuovo verso la meta ormai vicina.”

“...

the carriage stopped; a feeble ringing was heard and a priest

carrying a chalice with the Blessed Sacrament appeared from a corner;

behind him followed an altar boy, who held a white umbrella

embroidered in gold over his head; in front of him another held a

large lighted candle in his left hand, and with his right he waved a

silver bell, very much amusing himself. A sign that one of those

barred houses enclosed an agony, it was the Holy Viaticum (Last

Sacrament). Don Fabrizzio got out, knelt on the pavement,

the ladies made the sign of the cross, the bells disappeared in the

alleys that rushed towards S. Giacomo, the calèche with its

occupants, burdened with a salutary warning, set off again towards

the destination, now quite close."

What

does a man do, even if he were to be a “Leopard”, when he

realizes that youth has gone for ever, that the sensual pleasures have

lost their intoxicating initial splendour, and no longer

constitute the compass of daily life?

He

does as follows:

Final

scene of the film: Il Principe de Salina, having...

kneels down in a modest suburb of Palermo. In the novel this scene

comes before the Salina family arrives at the ball, not after.